Psychopathy: The Problem

Why we need a new framework for understanding psychopathy, narcissism, and related presentations

This is the first article in a series on understanding psychopathy and related presentations. The series is written for three audiences: people with psychopathic or narcissistic traits who want to understand themselves better, clinicians and researchers who want a more integrated framework, and curious laypeople who want to move beyond stereotypes.

Introduction

I’ve spent about a year trying to understand psychopathy – not just from textbooks, but from friendships. Some of my friends score high on the Psychopathy Checklist Revised (PCL-R), and through countless conversations, I’ve come to see that “psychopathy” is not one thing but many things hiding under a single label.

This creates problems. When researchers study “psychopathy,” they may be studying completely different populations. When clinicians treat “psychopathy,” they may be applying the same approach to people who need very different interventions. And when people try to understand themselves, they may find that the label fits in some ways but not others – leaving them more confused than before.

This series proposes a new framework: A multi-level taxonomy that distinguishes what you were born with, what your brain looks like now, what happened to you developmentally, what psychological structures you developed, how you behave, and how you understand your own agency. These are different lenses on the same phenomenon – and using all of them gives us a much richer picture than any single lens alone.

The Naming Problem

The word “psychopathy” is used to describe at least four different things:

1. Genetic loading. Researchers talk about genes associated with psychopathy – variants of MAOA, the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR), oxytocin receptor genes (OXTR), and others. When they say someone is “genetically psychopathic,” they mean the person carries variants that increase risk for psychopathic traits. (For reviews of candidate genes, see Gunter et al., 2010, Viding & McCrory, 2012, De Brito et al., 2021, and Frazier et al., 2019.)

2. Brain patterns. Neuroscientists describe psychopathy in terms of brain structure and function – a smaller or less reactive amygdala, reduced activity in the insula, altered connectivity between prefrontal and limbic regions. When they say someone is “neurologically psychopathic,” they mean the person’s brain shows these patterns. (See Fallon, 2013, Tyler et al., 2019, Frazier et al., 2019, for comprehensive reviews.)

3. Psychological structure. Psychodynamic clinicians describe psychopathy in terms of self-structure and relational patterns – an absent or fragmented sense of self, instrumental orientation toward others, absence of guilt or remorse, preoccupation with power or control. When they say someone is “psychodynamically psychopathic,” they mean the person has these internal structures. (See McWilliams, 2011, for a summary chapter and literature recommendations.)

4. Behavior. The PCL-R and similar instruments measure psychopathy through observable behaviors and self-reported traits – manipulation, callousness, impulsivity, criminal versatility. When they say someone is “behaviorally psychopathic,” they mean the person shows these patterns. (The PCL-R is described in Hare, 2008.)

Here’s the problem: These four things don’t always go together.

Someone can have genetic loading for psychopathy but, raised in a supportive environment, never develop the brain patterns or behavioral expression. Someone can develop psychopathic brain patterns through chronic trauma and dissociation, without any particular genetic predisposition. Someone can score high on the PCL-R through learned behavior, while having relatively intact empathic capacity that they’ve learned to suppress. And someone can have all the neurological and psychological features of psychopathy while never engaging in criminal behavior.

Using one word for all of these creates confusion. It leads researchers to treat heterogeneous groups as homogeneous. It leads clinicians to apply one-size-fits-all treatments. And it leads individuals to misunderstand themselves – either over-identifying with a label that only partially fits, or rejecting a label that captures something important about their experience.

The Heterogeneity Problem

Even within each level of description, there are important subtypes.

At the Genetic Level

Different genetic variants may produce different phenotypes:

Some variants (like low-activity MAOA) are associated with reduced emotional reactivity and may contribute to “cold” presentations.

Other variants (like short-allele 5-HTTLPR) are associated with increased stress sensitivity and may contribute to “reactive” presentations – though chronic stress can paradoxically lead to blunting over time.

Most psychopathy is probably polygenic – the result of many small-effect variants combining with environmental factors.

At the Neurological Level

The classic finding is hypoactivity in the amygdala and related structures – reduced fear conditioning, poor threat recognition, blunted emotional response. But there’s also:

Hyperactive patterns. Some individuals show increased amygdala and hypothalamic reactivity – hair-trigger threat response, reactive aggression. These “hot” presentations look very different from “cold” ones, even though both may be called psychopathic.

Dissociation-induced patterns. Some individuals developed normal or even hyperactive emotional responses early in life, but chronic trauma led to dissociative dampening. Their brains now look hypoactive, but the hypoactivity is secondary – and potentially reversible.

Mixed patterns. Some individuals show hypoactivity in some regions (e.g., amygdala) and hyperactivity in others (e.g., periaqueductal gray). These mixed presentations don’t fit neatly into simple categories.

At the Psychodynamic Level

The internal world of psychopathy varies enormously:

Some individuals have what might be called an “empty” self – minimal coherent identity, chameleon-like adaptation to context, observational relationship to their own behavior. (See my article on no-self psychopathy and M.E. Thomas’s memoir.)

Others have a “grandiose” self – inflated self-concept, need for domination, but with psychopathic features stabilizing the grandiosity against vulnerable collapse. I’ve previously called this combination sovereignism – a power-and-control orientation that differs from standard narcissism’s admiration-seeking.

Still others have developed extreme avoidant patterns – walled-off, nothing matters, independence as the only value.

And some are primarily organized around autonomy – hypersensitivity to any perceived constraint, rage or withdrawal when obligations are imposed.

At the Behavioral Level

The PCL-R distinguishes two factors:

Factor 1 (Interpersonal/Affective). Grandiosity, manipulation, callousness, shallow affect. The “cold” features.

Factor 2 (Lifestyle/Antisocial). Impulsivity, irresponsibility, early behavior problems, criminal versatility. The “hot” or chaotic features.

Some individuals are high on Factor 1 but low on Factor 2 – they’re manipulative and callous but not impulsive or reckless. Others show the reverse pattern. Still others are high on both. These are different presentations with different trajectories and different needs.

One of the most useful models in my opinion is the Triarchic Model of Psychopathy (Patrick et al., 2009), which distinguishes three distinct dimensions:

Boldness. Emotional resilience, social dominance, and low fear. (Roughly maps to N-hypoactive / Primary features.)

Meanness. Aggressive resource-seeking and lack of empathy. (Roughly maps to G-callous / D-predatory features.)

Disinhibition. Impulsivity and lack of restraint. (Roughly maps to Factor 2 / G-impulsive / Reactive features.)

This model is excellent because it acknowledges that “boldness” (fearless dominance) is distinct from “disinhibition” (impulsivity). A person can be bold without being disinhibited (the “successful psychopath”), or disinhibited without being bold (the “reactive” type). My framework builds on this by adding the developmental (E) and psychodynamic (D) layers that explain how these traits emerge and organize into a self.

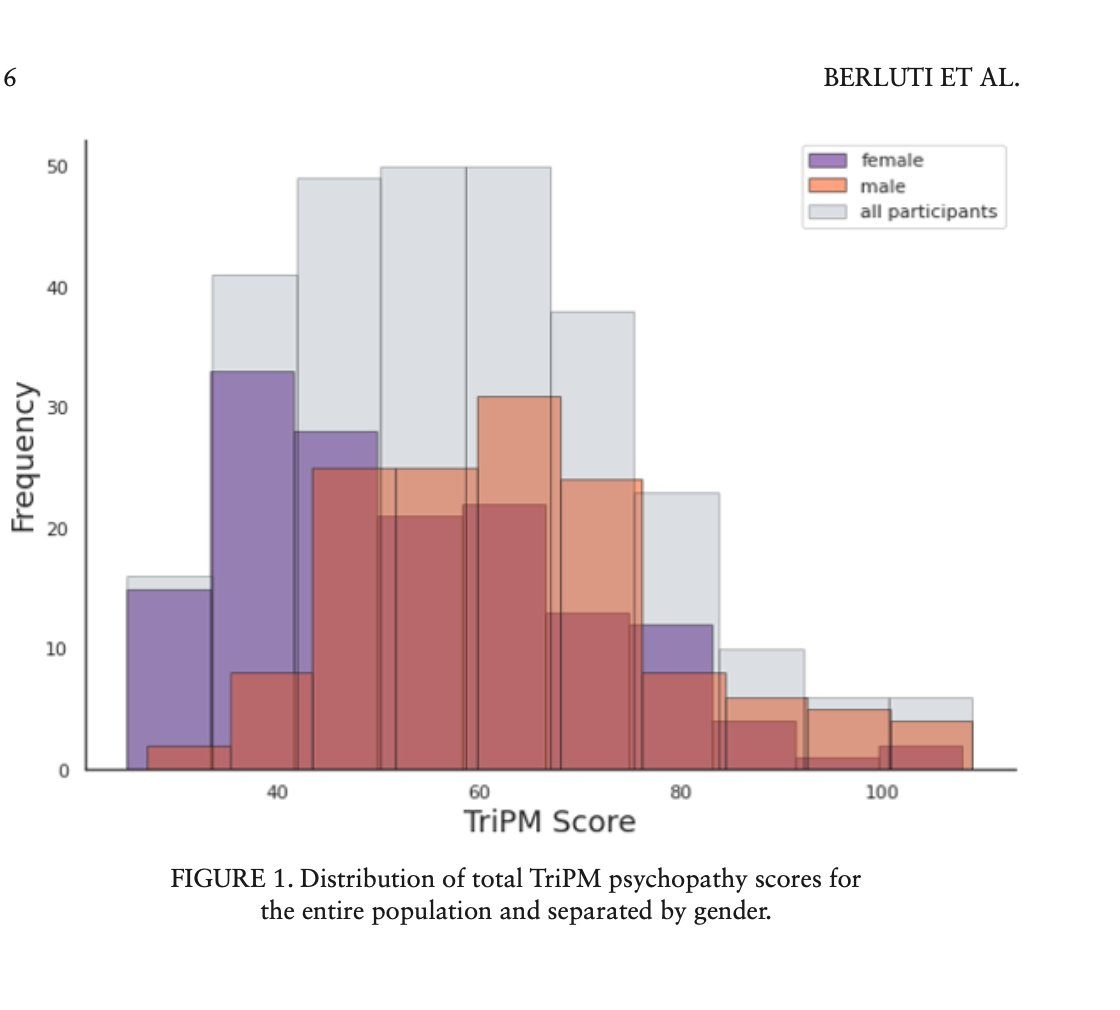

My score of 29 puts me in the 8th percentile among women (23 on boldness, 4 on meanness, 2 on disinhibition). The overall distribution in the general population varies greatly by gender.

Another study further subdivided these three factors for better predictive results in their sample (highlights mine):

From the majority of Boldness, Meanness, and Disinhibition scale items, respectively, emerged three factors reflecting: Positive Self-image, Leadership, and Stress Immunity; two factors tapping Callousness and Enjoy Hurting; and two factors involving trait Impulsivity and overt Antisociality. The emergent factors from the Boldness items were differentially intercorrelated with the other emergent factors, raising questions about the structural coherence of Boldness. Further, the Enjoy Hurting and overt Antisociality factors were more strongly correlated with one another than with the other scales from their home domains (Callousness and Impulsivity). All seven emergent factors were differentially associated with the external correlates, suggesting that the three original TriPM factors are not optimal for representing psychopathic propensity.

A third model is that of the Psychopathic Personality Inventory (a mock version that gives good results). It distinguishes 8 factors:

Machiavellian egocentricity. A ruthless and self-centered willingness to exploit others.

Social potency. The ability to charm and influence others.

Coldheartedness. A distinct lack of emotion, guilt, or regard for others’ feelings.

Carefree nonplanfulness. Difficulty in planning ahead and considering the consequences of one’s actions.

Fearlessness. An eagerness for risk-seeking behaviors, as well as a lack of the fear that normally goes with them.

Blame externalization. Inability to take responsibility for one’s actions, instead blaming others or rationalizing one’s behavior.

Impulsive nonconformity. A disregard for social norms and culturally acceptable behaviors.

Stress immunity. A lack of typical marked reactions to traumatic or otherwise stress-inducing events.

They are (with the exception of coldheartedness) sometimes grouped into “fearless dominance” and “self-centered impulsivity.”

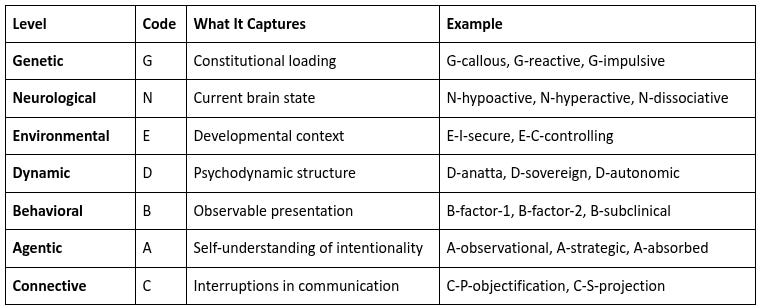

The Framework: G-N-E-D-B-A

To address these problems, I propose a multi-level framework with six dimensions:

Each individual can be described as a profile across all six dimensions. Two people who both “have psychopathy” might have completely different profiles – and understanding those differences matters for prediction, treatment, and self-understanding.

The Ordering Is (Roughly) Causal

The dimensions are ordered from most distal to most proximal:

G (genetic) sets the constitutional foundation – what you were born with.

N (neurological) reflects the current brain state, shaped by G but also by experience.

E (environmental) captures the developmental context – what happened to you during critical periods.

D (dynamic) describes the psychological structures that developed from G, N, and E interacting.

B (behavioral) is the observable expression of D in action.

A (agentic) is how you understand and narrate your own behavior.

C (connective) describes typical interruptions in interpersonal communication, verbal or nonverbal.

This ordering helps us see that the same behavioral presentation (B) can arise from different developmental pathways (E) and different psychological structures (D), including different communicative failures (C), which in turn can arise from different neurological patterns (N) and genetic loadings (G). And all of this is filtered through how the person understands themselves (A).

Profiles, Not Labels

Instead of asking “Is this person a psychopath?” we can ask: “What is this person’s profile?”

For example:

Profile A. G-callous (genetic loading for reduced empathy), N-hypoactive (constitutional amygdala hypoactivity), E-secure-infancy + E-normal-childhood (good enough developmental environment), D-sadistic but regulated (sadistic interests channeled into consensual outlets), B-subclinical (no behavioral problems). This person has constitutional psychopathy but developed well – they’re functional, may not even identify as having any disorder because they function at the neurotic (healthy) level of personality organization.

Profile B. G-minimal (no particular genetic loading), N-dissociative (secondary blunting from chronic dissociation), E-disorganized-infancy + E-violent-childhood + E-controlling-childhood (severe mixed adversity), D-sovereign + D-sadistic (power-oriented, ego-syntonic sadism), B-mixed (high on both PCL-R factors). This person developed psychopathic features defensively – and the key question is whether those features are reversible.

These two individuals might be called “psychopathic” by different psychologists but they are fundamentally different. Understanding the difference matters for predicting their trajectories and for any treatments they may or may not attempt.

What This Series Will Cover

This series will develop the framework in detail:

Article 2: The Substrate. Genetics and neuroscience – what we know about the biological foundations of psychopathy, and how to think about primary versus secondary presentations.

Article 3: The Shaping. Environment and development – how different types of adversity lead to different outcomes, and why the same genetic loading can produce a functional person or a criminal depending on context.

Article 4: The Self. Psychodynamic structures – the different ways the psychopathic self can be organized, including the autonomy dimension and the relationship between psychopathy and narcissism (what I’ve called sovereignism).

Article 5: The Mechanics. How empathy fails – a detailed breakdown of the different ways empathy can break down, from perceptual failures to simulation failures to affective inversion. (This connects to my earlier work on the sadism spectrum.)

Article 6: The Types. Archetypal clusters – common profiles that tend to co-occur, with recognizable presentations that readers may identify with.

Article 7: The Choice. Recovery, if you want it – an honest assessment of what recovery means for different presentations and the trade-offs involved.

A Note on Tone

This series is written for three audiences, and the tone reflects that.

For people with psychopathic or narcissistic traits. I’m not here to moralize or to tell you you’re broken. I think that factory farming is an abomination akin to slavery but at a massively greater scale and that the cuts to USAID are crimes against humanity worse than many wars. Most people are oblivious to that or contribute to it. The median serial killer vanishes in the statistical noise among the horrors of this world. Many of my psychopathic friends are actually doing better than average despite their traits, or perhaps precisely thanks to what they had to learn to make these traits work for them. If they donate $100 to an ACE top charity, they’re suddenly among the crème de la crème of the least harmful humans alive.

So if that fucked-up ne’er-do-well that’s the median person deserves my honesty and respect, so do you. I’ll describe things as they are, including trade-offs that others might not acknowledge. Empathy is fun but also painful and often detrimental to moral decision-making. Regulation is stabilizing but also boring. Attachment creates meaning but also vulnerability. These are real trade-offs, and I’ll respect your intelligence enough to present them honestly.

For clinicians and researchers. I’ve tried to integrate findings from neuroscience, genetics, attachment theory, and psychodynamic thinking into a coherent framework. I’ll provide references throughout and a technical glossary. The clusters I propose are hypotheses, not established facts – but they may help organize thinking about a heterogeneous population.

For curious laypeople. I’ll explain technical concepts as I go and provide examples (real and fictional) to make abstract ideas concrete. You don’t need a psychology background to follow this series.

One thing I won’t do is pretend that all presentations are equally concerning or that change is always desirable. Some people with psychopathic traits live excellent lives and contribute enormously to society. Others feel isolated, desolate, hopeless, or cause significant harm. The framework I’m proposing is descriptive, not prescriptive – it’s about understanding, not judging.

Glossary: Key Terms for This Series

This glossary introduces terms used throughout the series. Full definitions are provided in the relevant articles.

Dimensional Levels

G (genetic). Constitutional loading from genetic variants. Examples: G-callous, G-reactive, G-impulsive.

N (neurological). Current brain state, including structure and function. Examples: N-hypoactive, N-hyperactive, N-dissociative.

E (environmental). Developmental context across life stages. Subdivided into E-I (infancy), E-C (childhood), E-P (puberty), E-A (adult entry).

D (dynamic). Psychodynamic self-structure and relational patterns. Examples: D-anatta, D-sovereign, D-autonomic.

B (behavioral). Observable presentation. Examples: B-factor-1, B-factor-2, B-subclinical.

A (agency). How the person understands their own intentionality. Examples: A-observational, A-strategic, A-sovereign.

C (connective). What typical perception and mentalization failures interfere in the interpersonal functioning of the person. Examples: C-P-aversion, C-S-no-self, C-A-suppressed.

Key G-Level Concepts

G-callous. Genetic loading for reduced empathy, reduced fear, and blunted emotional reactivity.

G-reactive. Genetic loading for emotional reactivity, stress sensitivity, and dysregulation.

G-impulsive. Genetic loading for impulsivity, sensation-seeking, and disinhibition.

G-minimal. Minimal genetic loading for psychopathic traits.

Key N-Level Concepts

N-hypoactive. Reduced activity in amygdala, insula, and related structures; constitutional low reactivity. The “cold” pattern.

N-hyperactive. Increased reactivity in amygdala, hypothalamus, and periaqueductal gray; reactive aggression. The “hot” pattern.

N-dissociative. Secondary blunting from chronic dissociation; originally reactive, now dampened. Key marker: The person remembers being different.

N-disconnected. Reduced connectivity between prefrontal and limbic regions.

Key E-Level Concepts

E-I (Infancy, 0–2 years). Attachment formation. Key variants: E-I-secure, E-I-avoidant, E-I-preoccupied, E-I-disorganized.

E-C (Childhood, 2–12 years). Moral development, socialization, self-concept. Key variants: E-C-unattuned, E-C-neglect, E-C-punitive, E-C-violent, E-C-controlling, E-C-parentified, E-C-golden, E-C-scapegoat.

E-P (Puberty, 12–18 years). Identity, peers, autonomy. Key variants: E-P-peer-success, E-P-peer-failure, E-P-antisocial.

E-A (Adult entry, 18–25 years). Pathway into adult life. Key variants: E-A-success, E-A-privilege, E-A-crime, E-A-addiction, E-A-unstable.

Key D-Level Concepts

D-anatta. An empty or absent sense of self; minimal coherent identity. (From the Buddhist concept of anattā, “no-self.”)

D-sovereign. Power-and-control orientation; combines narcissistic grandiosity with psychopathic callousness and sadism. See sovereignism.

D-autonomic. Hypersensitivity to perceived constraints on freedom; autonomy as a core value. Reactive (not proactive), non-narcissistic, non-sadistic version of D-sovereign.

D-narcissistic. Unstable self-esteem; real or inverted grandiosity; need for specialness or admiration.

D-avoidant. Extreme dismissive attachment; walled-off; nothing matters.

D-echoist. Self-effacing orientation; meeting others’ needs at the expense of one’s own.

D-secure. A stable self without any psychopathy-associated traits.

Key B-Level Concepts

B-factor-1. High on PCL-R Factor 1 (interpersonal/affective): grandiosity, manipulation, callousness, shallow affect.

B-factor-2. High on PCL-R Factor 2 (lifestyle/antisocial): impulsivity, irresponsibility, early behavior problems, criminal versatility.

B-mixed. High on both factors.

B-violent. Violence as a prominent behavioral feature.

B-subclinical. Trait-level features; functional; doesn’t meet clinical thresholds.

B-normal. Low to average levels of behavioral traits.

Key A-Level Concepts

A-observational. “I watch myself do things.” Minimal sense of deliberation; actions emerge from observation.

A-strategic. “I plan, then act.” Genuine prospective intentionality.

A-narrativizing. Real-time rationalization; maintaining a running story about what you’re doing.

A-retroactive. Post-hoc rationalization; acting first, explaining later.

A-selective. True-but-partial explanations; picking one motivation and presenting it as the whole story.

A-externalizing. Locating causation externally; “They made me do it.”

A-absorbed. Taking responsibility for others’ actions; “It’s my fault they hurt me.”

A-amnestic. Forgetting ego-dystonic actions, or not being able to access the memories while they’re ego-dystonic.

Key C-Level Concepts

C-P-…. Failures of the perception of distress.

C-S-…. Interruptions of cognitive empathy or mentalization.

C-A-…. Deficits of affective empathy.

C-M-…. Interruptions related to the motivation to act.

C-B-…. Disinhibition on the level of the behavior.

Key Distinctions

Primary vs. secondary. Primary presentations were “always this way” – constitutional, from early development. Secondary presentations developed later, often as a defensive response to trauma, and may be more changeable.

Factor 1 vs. factor 2. The two factors of the PCL-R. Factor 1 captures interpersonal and affective features (manipulation, callousness). Factor 2 captures lifestyle and antisocial features (impulsivity, criminality).

Ego-syntonic vs. ego-dystonic. Ego-syntonic traits feel consistent with one’s self-image and values; ego-dystonic traits feel foreign or distressing. Sadism that feels “right” is ego-syntonic; sadism that causes guilt is ego-dystonic.

Next: The Substrate

The next article explores the biological foundations of psychopathy – what genetics and neuroscience tell us about the origins of these presentations, and how to think about the critical distinction between primary and secondary forms.