Psychopathy: The Choice

Recovery, if you want it

This is the final article in a series on understanding psychopathy. Previous articles covered the framework, biology, environment, psychological structure, empathy mechanisms, and archetypal clusters. This article explores recovery – without moralizing and with attention to what’s actually possible and what it costs.

Introduction

This article is for people who want to consider change. That’s not everyone. Some people with psychopathic traits are perfectly content and functional. Some don’t experience their traits as problems. Some have built lives that work for them as they are.

If that’s you, this article isn’t a prescription. But if you’re curious about what’s possible – or if you’re experiencing distress and wondering what might help – this is an honest assessment.

Dimensions of Recovery

Recovery isn’t one thing – it’s multi-dimensional. Different dimensions matter for different presentations, and each dimension has trade-offs.

Stable life and environment

Emotional regulation and behavioral control

Insight and mentalization

Integration of self-states

Developing prosocial values

Capacity for guilt

Capacity for remorse

Access to affective empathy

Capacity for secure attachment

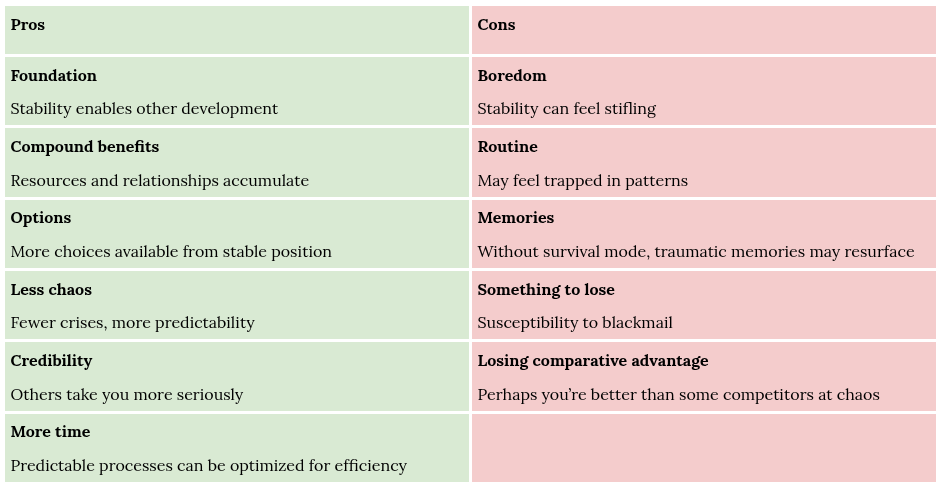

Stable Life and Environment

What it means. Achieving stable circumstances – housing, social environment, employment, relationships, legal status, enemies.

Assessment

Stability is almost pure upside for most people. Without stability, it’s often necessary to move from hotel to hotel and from country to country, which makes it hard to plan more than a few weeks ahead. That interferes with collaborative efforts such as most paid work. It also increases the cognitive load trying to learn how the local infrastructure works, time and effort that could be spent on efforts with exponential yields (healing, investment, education, networking, getting criminal records sealed).

Financial stability also makes things cheaper in the long run – fixed-interest mortgage instead of rent, up front payment instead of installments, no high-interest debt, etc. – and has exponential yields.

The worst case is if you’re still stuck in the environment (often the family) that produced your adaptation in the first place. For many people, their parents’ home is a battlefield where they’re trying to survive behind enemy lines. Most of the world (outside war zones) is not like that. In most cases it’s beneficial to get out of there, if at all possible, and gradually adjust to society rather than to code-switch between environments.

The environment one is stuck in can also be one of crime. The resulting availability of crime-based income sources can perpetuate a cycle of crime -> prison -> criminal records -> difficulty finding work -> more crime. Removing oneself from these networks, if possible, will make life harder in the short term but promises and eventual breaking of that cycle. The proximity to crime also increases the risk of wrongful convictions: Some jobs might have a low risk of legal consequences, but someone in your environment might still accidentally or intentionally implicate you in their crimes.

Chaotic environments – whether at home or in criminal contexts – also often come with violence. Depending on the health system in your country, that can be another unpredictable source of tremendous costs, on top of legal fees. Building wealth or maintaining a good credit rating can be difficult as a result.

Finally, stability makes it easier for others to rely on you. Even if they trust your intentions, they’ll need to take into account the risk that you’ll drop your collaborative project because you have to leave the country from one day to the next, end up in jail or in a hospital for weeks or months, lose your car, power, or internet connection, etc.

However, people who love chaos for the thrill (or conversely to beat the boredom) may need to find replacement activities that are thrilling while not threatening some basic stability – a job that is action-packed in itself, anything to do with one’s phobias, BDSM, the sorts of hobbies you can get a RedBull documentary out of. Especially if chaos is one’s comparative advantage, jobs that deal in chaos – like politics or sometimes law – may be attractive.

People who’ve been maintaining their chaos to repress traumatic memories, may need to process those once the chaos has died down. That’s a good investment in the long run.

Building stability in the long run means having something to lose. That’ll generally make you most trustworthy for others, but at the cost that you do indeed have something to lose. Some possible actions will become more costly in expectation.

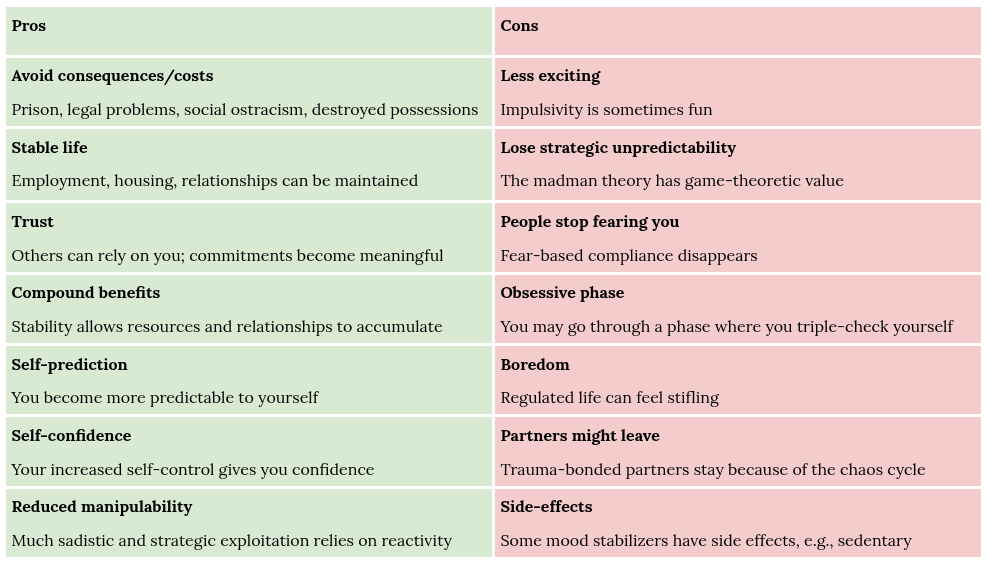

Emotional Regulation and Behavioral Control

What it means. Developing the capacity to control behavior – to pause before acting, to resist impulses, to maintain consistent conduct.

Assessment

Emotional or behavioral regulation is another very popular recovery step. The benefits compound over time; the costs are real but manageable.

Impulsive decisions often lead to particularly badly executed crimes, manipulability, losing friends and partners, and costs from having to replace damaged possessions. That includes costs from impulsive physical and verbal aggression as well as unpredictable ghosting, moves to other countries, and continual deleting and recreating of social media accounts.

The benefits compound: healing, savings, education, networking, etc. Much like above.

An added benefit is that those who care deeply about self-control can derive self-esteem from their increased ability to know what they’re going to do in the next moment and years down the line.

The madman theory point is worth acknowledging: If you’re unpredictably dangerous, people are less likely to push you even in minor ways because you might just react in (to both of you) irrationally costly ways. Regulation sacrifices this. For some, that’s a loss of a strategic advantage.

Sadly some relationships only persist because of the chaos cycle. If you regulate, those relationships may end – which might be good for both parties, but is still a loss.

Dialectical Behavioral Therapy is designed for emotional regulation and is considered to not have side-effects, but often drugs like mood stabilizers (lithium and others) are beneficial or even necessary for someone to be able to engage in therapy. These drugs can have side effects, though they vary from person to person, so it might be just about finding the right one (and the right dosage) for you.

With or without the assistance of drugs, you’ll probably go through a practice phase where you’ll still have to think long and hard how to react most effectively in a given situation. That becomes more automatic over time, but the hesitancy may persist beyond its usefulness. That too is a transitory phase.

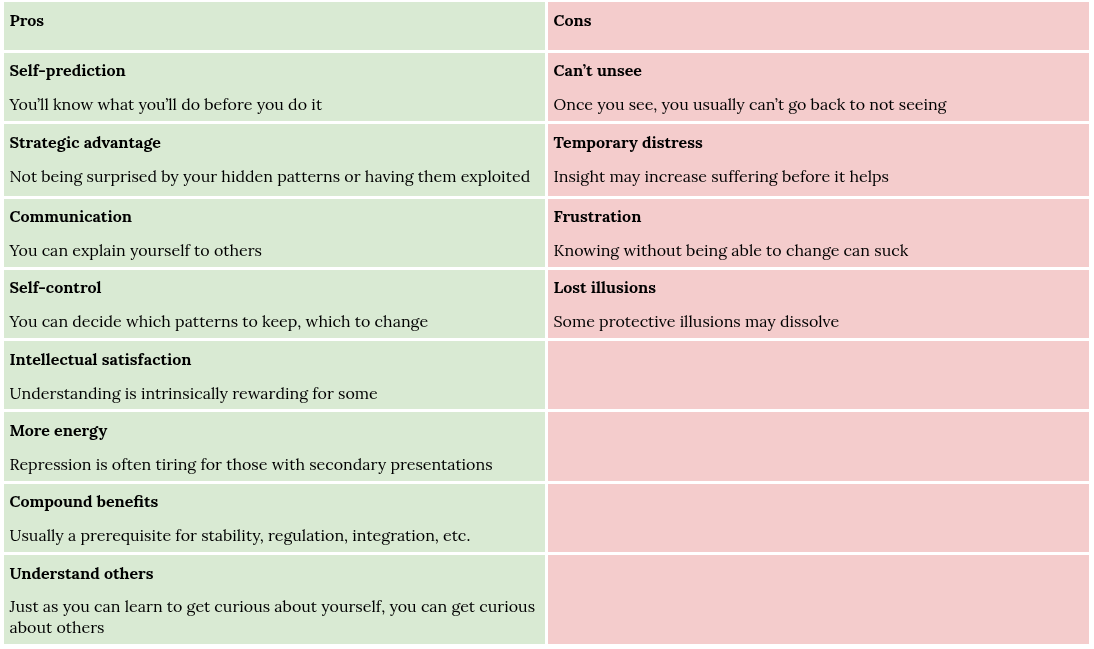

Insight & Mentalization

What it means. Understanding your own patterns and those of others – what you do, why you do it, what triggers you, what your mechanisms are.

Assessment

I’m generally a big fan of insight because it follows the principle of the Litany of Gendlin:

What is true is already so.

Owning up to it doesn’t make it worse.

Not being open about it doesn’t make it go away.

And because it’s true, it is what is there to be interacted with.

Anything untrue isn’t there to be lived.

People can stand what is true,

for they are already enduring it.

Insight is not only intellectually rewarding, it allows you to predict what you’ll do and is the foundation for changing it according to your will – i.e. many of the other choices in this article. If you don’t see it, others might, and then they can catch you off guard when they exploit your hidden vulnerabilities.

But most people are safe, so not only are vulnerabilities that you’re aware of ones that you can neutralize, all your self-knowledge, beyond vulnerabilities, is also what you can share with others to synchronize on expectations. Often being transparent about expectations up front is what gets the job done whereas the other would get pissed if they later showed up as a surprise.

All the skills that you learn to understand yourself better and better are mentalization skills. You can train those in mentalization-based treatment (MBT). You learn to get curious about yourself, form hypotheses of what might be going on with you given who you are and your current situation, test those hypotheses, and learn to accept the results without flinching. These are skills that you can also apply to others and to your interactions with them – they’ll hone your cognitive empathy. You’re probably quite different from most others, so to understand others, it’s critical for you to first understand yourself and how you’re different from others. More understanding strikes me as a fairly universally useful skill.

Lydia Benecke also observed that friends of hers who employ some kind of emotional repression mechanism (friends of hers with various psychopathic traits, probably excluding N-hypoactive presentations) get tired quickly during conversations with her. She hypothesized that these mechanisms are tiring for some. Conversely, not repressing anything, to the best of one’s ability, may unlock greater endurance.

The issues with insight all live at the intersection of awareness and paralysis. I’d choose awareness any day even if I cannot change something, but there is a certain frustration that comes with that. That frustration can be accepted, but I understand when some continue to choose comforting illusions over harsh reality.

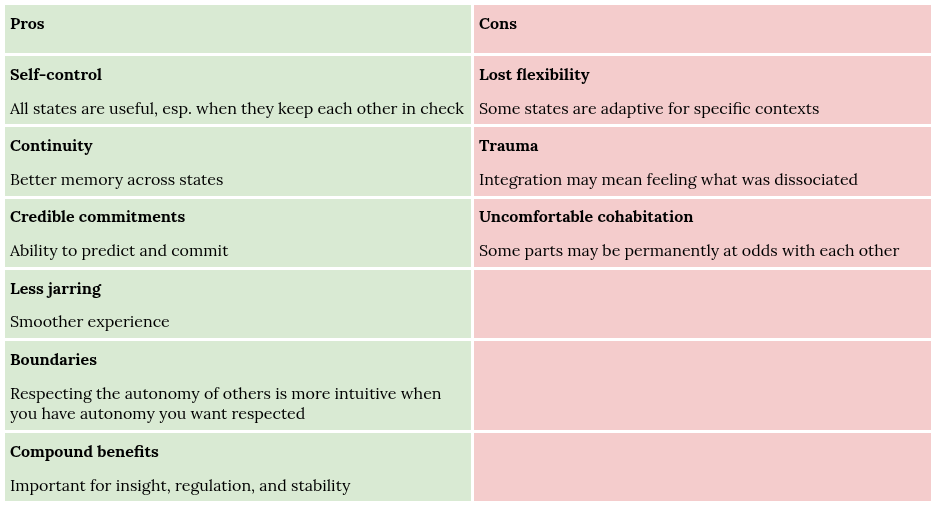

Integration

What it means. Bringing together fragmented parts of self – reducing state-switching, developing coherent identity.

Assessment

There is no separate dial “self-control” one can train; it’s always about integrating your interest in achieving more long-term goals with any short-term goals, and then finding a synthesis that you’ll also still appreciate much later. If your personality is split into an all-selfish part and a part that wants to be good to your friends, you can only be consistently good to your friends if you have uninterrupted access to the second one.

Some people have nothing that they could call their self. They have enough insight to know that they are vastly different people from one context to the next, or they have no access to who they are in the first place. This makes it difficult for them to intuit what it is like to have a coherent, continuous self. Even if they want to respect others’ autonomy or boundaries, they can’t intuit what that entails.

That also improves memory access. When parts are maximally separate, you can run into literal amnesia between them – you can only access the memories that are consistent with the expectations that the part has about who you are. In less extreme cases, the memories may be there, but they feel very abstract, like reading someone else’s diary. If you then try to imagine why you might’ve done whatever the “diary” says, you’ll confabulate very different reasons from the ones you had at the time. Or the memories may be there, but there’s a kind of anxiety that comes up when you try to recall them or get close to chat logs that might have the effect – perhaps an anxiety of not wanting to acknowledge the memories or an anxiety of not wanting to reactivate them lest you fall back into the self state that they’re associated with. In a fully integrated state, all of this is chill.

I can’t overstate the game-theoretic advantages of being able to commit credibly. The first advantage is low transaction costs. Jonathan Haidt writes in The Righteous Mind:

Social capital refers to a kind of capital that economists had largely overlooked: the social ties among individuals and the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that arise from those ties. When everything else is equal, a firm with more social capital will outcompete its less cohesive and less internally trusting competitors (which makes sense given that human beings were shaped by multilevel selection to be contingent cooperators). In fact, discussions of social capital sometimes use the example of ultra-Orthodox Jewish diamond merchants, which I mentioned in the previous chapter. This tightly knit ethnic group has been able to create the most efficient market because their transaction and monitoring costs are so low—there’s less overhead on every deal. And their costs are so low because they trust each other. If a rival market were to open up across town composed of ethnically and religiously diverse merchants, they’d have to spend a lot more money on lawyers and security guards, given how easy it is to commit fraud or theft when sending diamonds out for inspection by other merchants. Like the nonreligious communes studied by Richard Sosis, they’d have a much harder time getting individuals to follow the moral norms of the community.

But in an environment where high trust is possible (a sufficient fraction of the participants are trustworthy), it also becomes individually rational to be trustworthy! That’s because of gains from trade in iterated games.

One diamond seller has lots of diamonds and needs to pay rent for their store. I don’t have any diamonds but I have a buyer who wants me to select one for them. A trade happens when the seller values the diamond less (abundance, rent) than I do (rich buyer, time pressure). Both of us generate gains from trade by executing it, generating net wealth in the world.

My profit is small in each trade, but I can repeat these trades infinitely many times, for hypothetically infinite profits. It’s just a matter of how long one can maintain the streak. Conversely, stealing the diamond would foreclose any future trades for a hypothetically infinite loss. This introduces a strong positive feedback effect in favor of high trust.

In practice the profits aren’t literally infinite because the seller might retire or we might die. If the seller is less reliable, that will curtail the potential future profits. Same from the seller’s perspective if you are unreliable. If the transaction costs are high due to security measures, that also reduces the profits either of us can make by maintaining the streak. Both factors mean that we both have less to lose, and so can trust each other less. This introduces a strong negative feedback effect in favor of betraying the trust.

High-trust environments make everyone (in aggregate and individually) richer. Low-trust environments make everyone poorer. So it makes sense to seek out high-trust environments and then to play by their rules until you get bored of getting rich.

That brings us to the importance of integration for your choice of environment. Integration is important to function in a high-trust environment and a high-trust environment is necessary if further recovery is desired.

Which brings us to the greatest con of integration: You’re probably already well adapted to low-trust environments, so if you have to continue to function in one – your family, social circles, etc. – integration is no use. It would only give you access to memories and perhaps feelings you don’t want to access, and allow the parts of you to enter into the tug of war that you get when you have parts that often want contradictory things – thrill-seeking vs. surviving to provide for your kids; sadism vs. being good to your friends. Those fights can eventually be settled from what DBT calls the wisemind stance, but it takes practice to get there.

Sidenote: Credible commitments are such a powerful weapon that it’s often good that we usually can’t just credibly commit to anything. Open source game theory is a branch of game theory that studies what would happen if we could fully credibly commit – like throwing out the steering wheel in a game of chicken in a way the opponent can’t miss. The results include commitment races, where everyone tries to be first to commit.

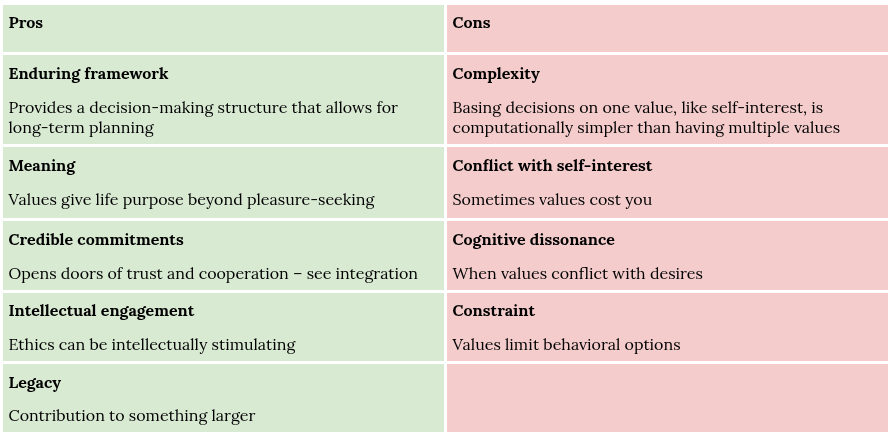

Values

What it means. Developing an ethical framework – principles that guide behavior independent of emotional responses.

Assessment

Where integration provides the scaffolding, values provide the content. A value of reliability is what unlocks the gains from trade from the previous section. A value of respecting others’ autonomy enables respectful relationships. A value of authenticity prevents you from self-deceiving. A value of minimizing harm makes me happy, because I’m a suffering-reducer.

Importantly, values are your own. As you gain more insight, you discover what you actually care about, or at least what feels right to the point where you can commit to it. Brené Brown has compiled a long list of values to choose from or to amend. It makes sense to focus on just the most important core values. (Feel free to call them standards or moral safeguards or whatever other terms suit you best.)

A friend of mine who generally has a choice whether to go into a D-avoidant-type psychopathic state or not indulged in it for five years but found the boredom some excruciating that she even chose her alternative BPD state over it. Values provided her with a purpose in life and the opportunity to contribute to something larger that she cared about. Without it, she didn’t feel like she had a life worth living.

Personally, ethics has been a special interest of mine for decades, so I also find it stimulating to argue for metaethical expressivism over realism, or for antifrustrationism over hedonic act utilitarianism.

Conversely, though, different values often trade off against each other, which introduces complexity in proportion to the number of values involved. Self-interest is just one of them, so the trade-offs will sometimes conflict with it. Finally, all the game-theoretic advantages of credible commitments constrain behavior ipso facto.

Below I mention the function of guilt for training values. For many, certainly G-callous + N-hypoactive presentations, that’s not the most direct way to get there since it might just be very hard to train any capacity for guilt. So if you’re interested in values, relying on habits and on making them part of your identity is the more direct path.

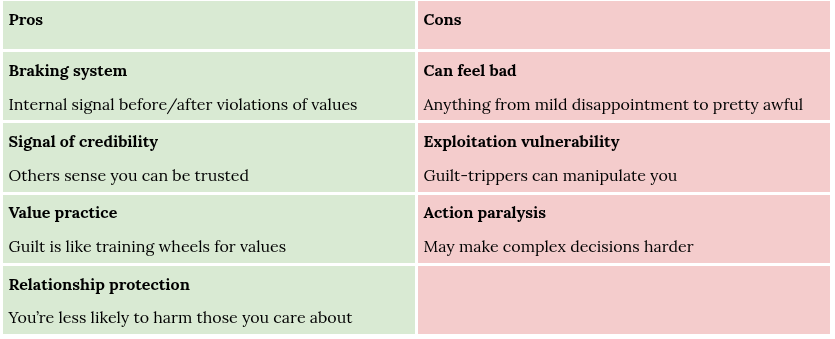

Guilt

What it means. Developing the capacity to notice when you violate your values and learn from it.

Assessment

Guilt is a signal, not a virtue. If you already don’t want to harm people you care about, and you have other mechanisms (values, regulation, foresight) to prevent harm, guilt adds suffering without adding benefit. But if you keep accidentally violating your values, guilt will help you notice it earlier and stop sooner.

Disambiguation: I understand guilt to be the name for the emotion you feel if you violate your own values – say, if you have a value of respecting other’s autonomy, but then you get carried away or overlook something, and someone else does get hurt. It’s similar to a kind of disappointment in yourself but with some added (alarm) bells and whistles. I understand remorse to be the name of the emotion you feel when you do something that makes someone else feel harmed by you.

So when you notice that you keep running into unwanted consequences of your actions, and you find that you already have values in place that should prevent you from taking these actions, and you have sufficient integration that the parts who care and not wholly separate ones from the parts who act, then guilt is helpful as a signal for your practice. It’s like a climbing coach who tells you how to optimize your body positioning on the wall to optimize your climbing performance.

If you’re already doing a good job following your values, guilt doesn’t help boost that further.

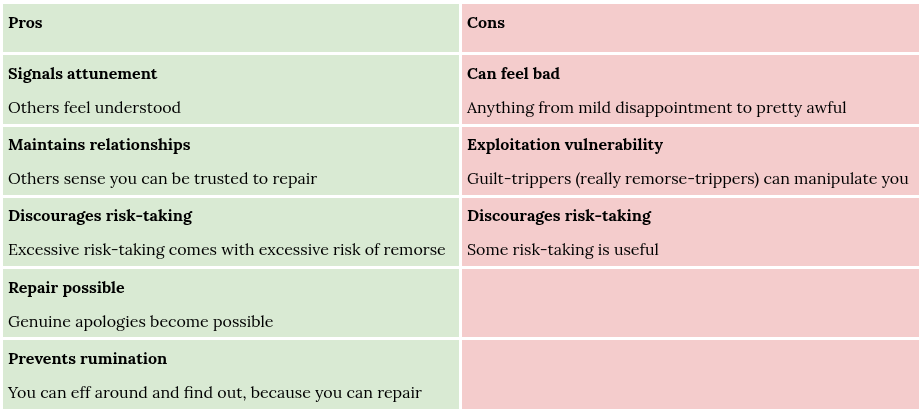

Remorse

What it means. Developing the capacity to feel the need to make it up to someone when you’ve made a mistake.

Assessment

This is one of my favorite moral emotions. As clarified above, this is about the other person and whether they feel harmed by you – regardless of whether you’ve followed your values or violated them. You’ll always make mistakes, so it won’t stop being useful.

Core to parenting is what is called “contingent marked mirroring”: The “contingent” part means that you mirror back the emotion of the other person to make them feel understood. The “marked” part means that you evaluate the situation and communicate our evaluation too. For example, if the kid is hurt and crying, the parent may first express empathy with the hurt of the child (this can be completely fake, so long as it’s accurate), and then soothe the child to signal that the bruise is not dangerous.

This is also important when you’re interacting with adults: If you’ve just lost your temper with someone and they look scared, you can say, “Oh my god, I’m sorry, I didn’t want to scare you!” That’s an emotionally charged response that meets them where they are but also signals that you understand that they feel scared. Then you can follow it up with, “I’ll try hard not to let that happen again. Do you need space or a hug? Or ice cream?” That signals that you’re drawing lessons from what happened and are ready to repair. Your friend or partner may have particular preferences for this.

This can feel scary for some because you’re admitting that you’ve made a mistake, and the other can now hold that against you. It’s like you’re indebted to them, and you’re telling them about it. Hence it’s important to keep the repair proportionate. If you’ve broken something, you replace it; if you’ve scared someone, you make sure to make them not scared anymore; if you’ve stolen something, you give it back. If they keep holding it against you for ages when you’ve tried your best to make amends, it’s their turn to show remorse for their exploitative behavior.

Hence remorse needs to be proportionate. It can allow you to be spontaneous and risk-taking because you know you’ll make it up to whoever you might hurt and you won’t lose friends if you make a mistake. It can also curb excessive risk-taking if the possible consequences are things that would be costly or impossible to repair. But it can also have the opposite effect of stifling healthy risk-taking if the prospective remorse is disproportionate.

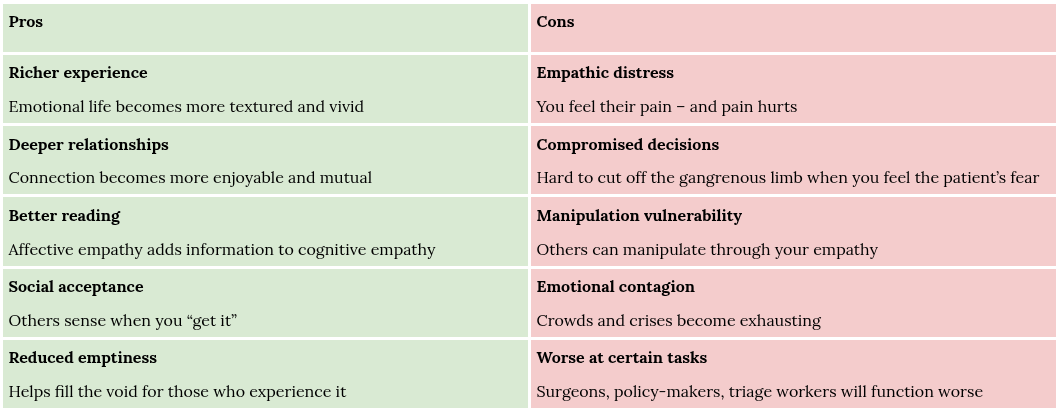

Affective Empathy

What it means. Developing or restoring the capacity to feel what others feel – to have their distress produce distress in you, their joy produces joy.

Assessment

Affective empathy is quite a mixed bag. Sometimes I love it; sometimes I resent it. I love it when I spend time with my partners. I resent it when it encourages me to look away from the overwhelming suffering in the world. Plus many of my friends act morally without empathy. They have values, insight, and regulation. They channel their sadism (if any) into consensual outlets. They don’t need empathy to be a good person – and developing it would have costs they don’t need.

I agree with Paul Bloom and his book Against Empathy: Empathy is fun, but unnecessary for and often detrimental to moral decision-making.

When I chat with my friends with NPD and see how they struggle in romantic contexts, I feel how scared they are, I feel the anger of their partners, and I feel my own exasperation over how unnecessary these conflicts feel from my vantage point. When they make progress and acknowledge that they’re not actually indifferent to their partners, I feel so proud of them. When they’re grateful for something I’ve helped them overcome, I feel so happy for them. When I repair with my partners and feel how nervous they were before and how safe they feel again, it’s also heartwarming. I’d never want to miss all this vibrancy in my life again.

For those who feel a lot of boredom or emptiness, all this vibrancy would probably also go a long way to keeping them entertained.

But god I have to work so hard to stay motivated for my charity work. The greatest perils in the world are not kids dying from cancer or abandoned cats, because there are at most millions of them and it’s expensive to try to help them more than they’re already being helped. The greatest perils are animals in factory farms, fish and shrimps in aquaculture, farmed insects, animals dying in wilderness from diseases, parasites, starvation, and predation, global catastrophes and more, because there are easily a trillion times as many. Affective empathy doesn’t work for large numbers. You’d expect to care a million times more for a million people than for one, but empathy probably makes you care less. Worse, when you put in the work and save a million animals from suffering, empathy doesn’t even reward you for that. In this regard, it’s a complete scam.

If you want to make great career decisions to help the world, make great impactful donations, design great policies, then you better turn off your affective empathy. Compassion (karuna) doesn’t require affective empathy either. If we want to help at all, we have to triage constantly because we can’t help everyone. Empathy is only in the way of efficient triage. And that doesn’t even touch on intentional manipulation and the things people with high preoccupied attachment do intuitively to tug on other’s heartstrings.

So empathy is a really mixed bag. There be dragons. Enter at your own risk.

Note that even my untraumatized, non-disordered, securely attached friends with G-callous and N-hypoactive don’t have access to affective empathy. They tend to feel guilt and remorse very lightly and affective empathy not at all. Don’t be discouraged by that – but relying on habits and identity to practice values may be a quicker route to success if that’s what you’re interested in.

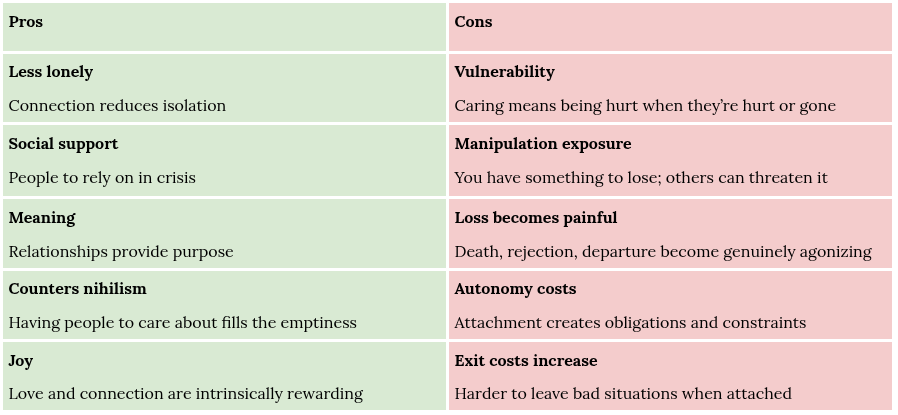

Attachment

What it means. Developing the capacity for genuine emotional connection – to care about specific people, to be affected by their presence and absence.

Assessment

As someone with mildly above-average preoccupied attachment and very low avoidant attachment, I love attaching to people. It makes me feel safe, supported, and needed. Living alone is not fun for me. Meeting my friends and partners is what sparks joy.

But it’s crucial to attach to the right people. When someone strikes me as deeply genuine, my guard goes down quickly; when someone is reserved or has a history of interpersonal cruelty, I’ll keep my guard up for much longer.

Exposure to manipulation is a cost to me, so I can apply general risk management principles: What does the other have to gain, and how can I increase their cost to the point where the gain is no longer worth it for them while keeping my costs lower than the cost of the manipulation? This can mean taking things really slow, and seeing if they stick around.

The structure of the marketplace is also informative. If the attacker can gain $100 from exploiting you, it might seem like you’d have to invest enough into security to drive up their costs > $100, which might come at a cost of $10 to you. But that ignores that the marketplace may be such that there are plenty of people with sufficiently bad security that the attacker can extract $100 from them at a cost of $50 to them. So most likely, you can get away with investing $6 into your own security for a cost of $60 to the attacker, which is greater than what they’ll have to pay elsewhere. Then it’s no longer rational for them to pursue you as a target.

So attachment is not riskless, but the risks are manageable using standard practices.

Many people are afraid of getting duped just for the sake of the duping, even if it comes at no cost to themselves. Realizing that and worrying less about it can reduce avoidant attachment.

Another cost of attachments is the reduction in flexibility that comes with them as well as the time costs that need to be invested into the coordination. This is a common problem in startups who hire too many employees too quickly and get slowed down even on net by the coordination overhead. Hence there is a sweet spot where the overall joy, safety, and support that come with attachments is balanced against the coordination overhead. If your sweet spot is unusually high, you might consider polyamory. Long-distance relationships are another option to keep the costs from reduced flexibility low.

Finally, attachments can take on a bit of a life of their own, where against your better judgment you find it hard to break away from someone who’s not good for you. That’s a situation where it’s useful to have access to avoidant patterns and use them with discretion, i.e. not toward anyone or any romantic partner but specifically toward one person only.

And that’s it: The perhaps least romantic assessment of love ever written.

Conclusion

That’s the menu. If the cost-benefit ratios of any of these qualities strike you as desirable, you can train them yourself and employ a capable therapist to show you the ropes to speed things along.

Some cool types of therapy that I can recommend are Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), Mentalization-Based Treatment (MBT) and Schema Therapy. There’s also Transference-Focused Psychotherapy (TFP), which personally always rubs me the wrong way, but it’s also evidence-based.

You know best where your current bottlenecks lie, so you can tackle those first, then add whatever else you desire later on as the cherry on top.

If you have noticed any pros or cons that I have no listed, please let me know in the comments!

This completes the series on understanding psychopathy. Thank you for reading! If this framework is useful to you, I’d love to hear about it! If something doesn’t fit your experience, I’d love to hear about that too!

I haven't read the whole article, but it brought up a question – do you think psychopathy can be "healed"? I've never heard that before

It always sounded more like "this part of the brain is missing, that's why people are that way", but I also wondered about trauma induced stuff

Sorry if you already said all that stuff!