Psychopathy: The Substrate

Genes and brain: the biological foundations of psychopathy

This is the second article in a series on understanding psychopathy. The first article introduced the multi-level framework (G-N-E-D-B-A). This article covers the G (genetic) and N (neurological) levels – what you were born with and what your brain looks like now.

Introduction

When people ask “Is psychopathy genetic?” or “Is it in the brain?”, the answer is yes – but that’s not the whole story. Genetics and neurology form the substrate on which psychopathic presentations develop, but the substrate alone doesn’t determine the outcome. The same genetic loading can produce a successful surgeon or a convicted felon, depending on environment and development.

This article covers what we know about the biological foundations of psychopathy, with an emphasis on a distinction that matters enormously for understanding prognosis and intervention: primary vs. secondary presentations.

G-Level: Genetic Contributions

What We Know

Psychopathy has a heritable component. Twin studies suggest that callous-unemotional traits (a core feature of psychopathy) are moderately to highly heritable, with estimates ranging from 40% to 70% depending on the study and population. (See Viding et al., 2005, for an influential twin study.)

However, “heritable” doesn’t mean “genetic” in a simple sense. Heritability estimates include gene-environment correlations and gene-environment interactions. A child with genetic loading for psychopathy may also be more likely to experience certain environments (because their parents, who share their genes, create those environments) – and the genes may only express under certain environmental conditions.

Candidate Genes

Several genes have been associated with psychopathic traits, though findings are often inconsistent and effect sizes are small. (See Gunter et al., 2010, Viding & McCrory, 2012, De Brito et al., 2021, and Frazier et al., 2019.)

MAOA (Monoamine Oxidase A). The “warrior gene” – low-activity variants are associated with reduced breakdown of monoamines (serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine). The famous Caspi et al., 2002, study found that low-activity MAOA combined with childhood maltreatment predicted antisocial behavior. However, replications have been mixed, and the original finding may be smaller than initially thought.

5-HTTLPR (Serotonin Transporter). The short allele is associated with altered serotonin reuptake and has been linked to increased stress sensitivity. Paradoxically, chronic stress exposure in short-allele carriers can lead to emotional blunting over time – suggesting a pathway from reactivity to apparent hypoactivity.

OXTR (Oxytocin Receptor). Variants in the oxytocin receptor gene have been associated with reduced social bonding and empathy. Oxytocin is sometimes called the “bonding hormone,” and reduced signaling may contribute to the social detachment seen in psychopathy.

COMT (Catechol-O-Methyltransferase). The Val158Met polymorphism affects dopamine levels in the prefrontal cortex and has been linked to executive function, reward sensitivity, and impulsivity.

The Polygenic Reality

Most psychopathy is probably polygenic – the result of many genetic variants, each with small effects, combining with environmental factors. Recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have begun to identify polygenic risk scores for antisocial behavior, but these explain only a small fraction of the variance. (See Tielbeek et al., 2017, for a meta-analysis.)

The practical implication: There’s no “psychopathy gene.” Genetic testing won’t tell you if someone is a psychopath. What genetics gives us is a probabilistic loading – increased risk, not determination.

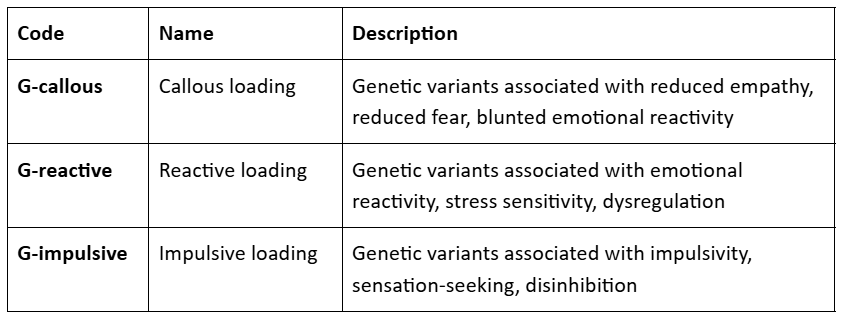

Parsimonious G-Level Categories

For the purposes of this framework, I propose three parsimonious G-level categories:

These can co-occur. Someone might have G-callous + G-impulsive, or G-reactive alone, or any combination.

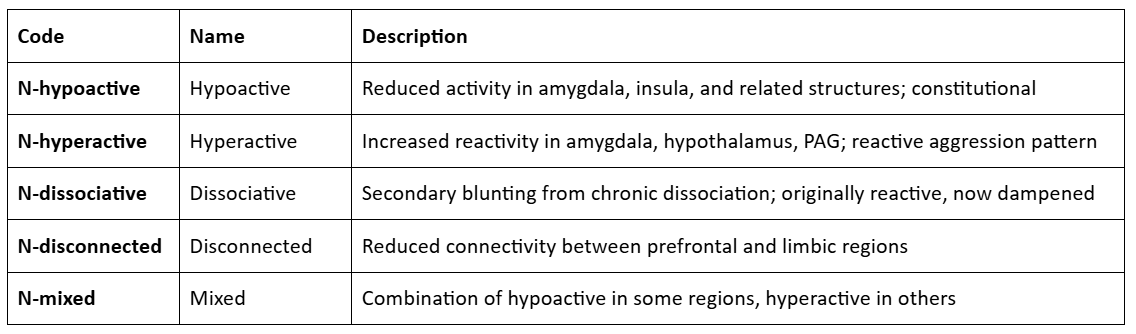

N-Level: Neurological Patterns

The Classic Finding: Amygdala Hypoactivity

The most widely known neuroimaging finding in psychopathy is reduced activity and/or volume in the amygdala – the brain region involved in fear processing, emotional learning, and threat detection. (See Blair, 2013, Blair, 2014, Fallon, 2013, Tyler et al., 2019, and Frazier et al., 2019.)

Individuals with amygdala hypoactivity show:

Reduced fear conditioning. They don’t learn to associate cues with aversive outcomes as readily.

Poor threat recognition. They’re less responsive to fearful facial expressions.

Blunted emotional response. Emotional stimuli produce less physiological and subjective response.

This pattern fits the “cold” presentation of psychopathy – the person who can lie without anxiety, harm without distress, and remain calm in situations that would terrify others.

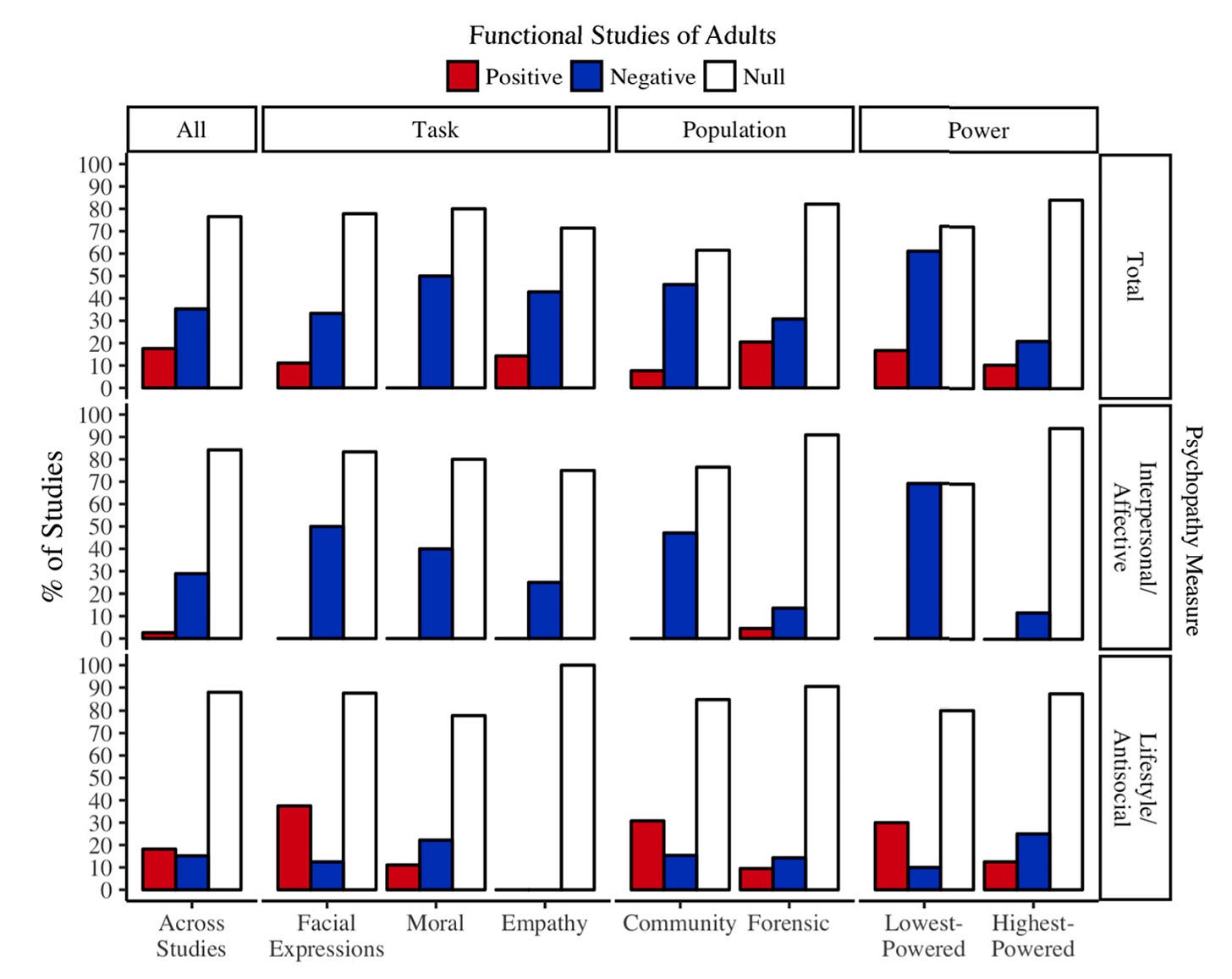

A systematic review basically bore out the finding that reduced amygdala function or size is associated with the “cold” presentation of psychopathy (the negative correlations in the second row above). The studies are confounded by mixing together different disorders under the label “psychopathy” and probably a host of other factors. For example, many fMRI studies are flawed, but structural MRI studies (finding smaller amygdalas) and quantitative fMRI studies (finding amygdala hypoactivity) are unaffected.

Beyond the Amygdala

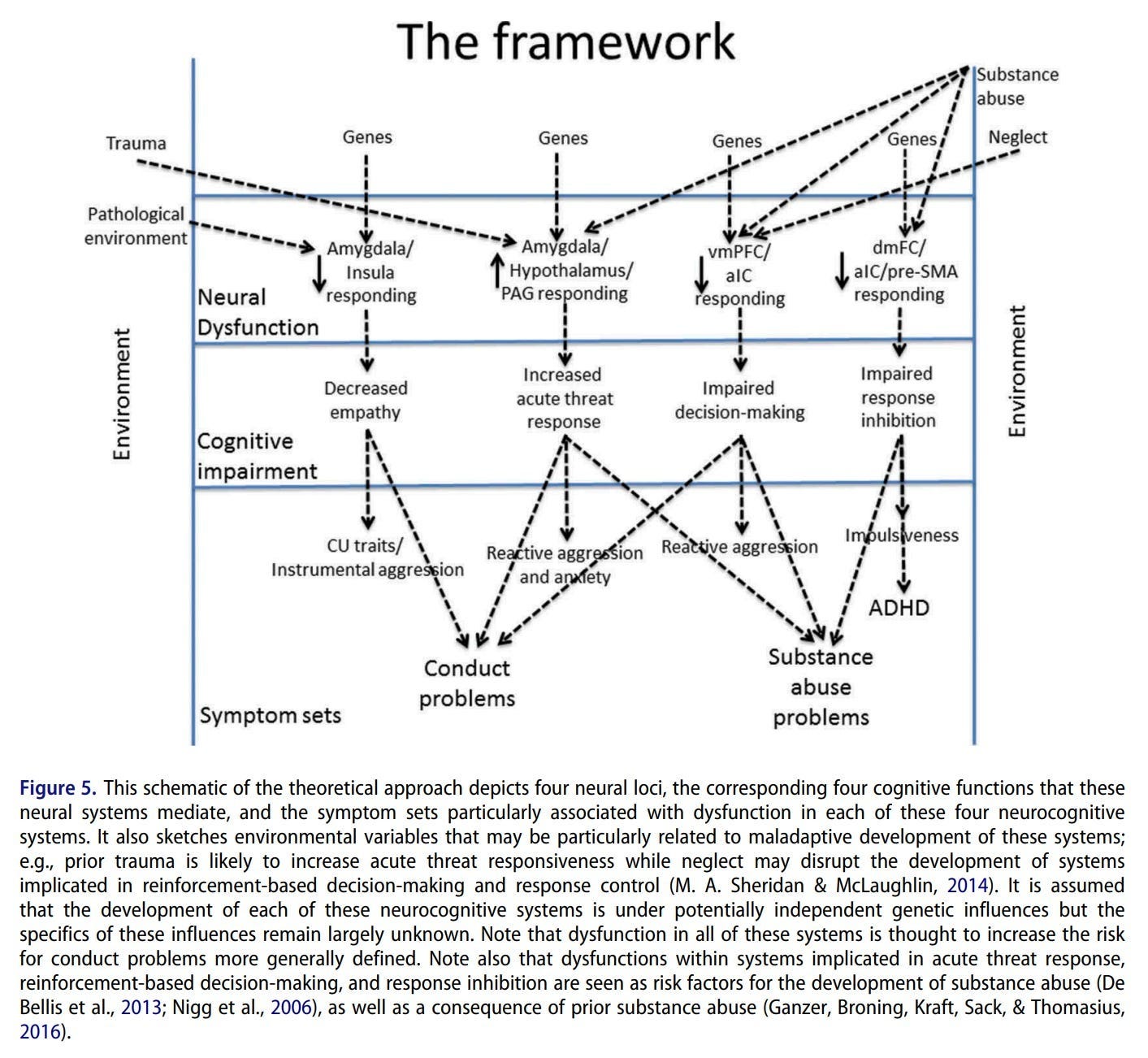

Other brain regions are also implicated in psychopathy. (See Blair, 2013, Blair, 2014, Tyler et al., 2019, and Frazier et al., 2019.)

Insula. The insular cortex is involved in interoception (awareness of bodily states) and empathic resonance (feeling what others feel). Reduced insula activity may contribute to the difficulty psychopathic individuals have in “feeling into” others’ experiences.

Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex (vmPFC). This region integrates emotional information into decision-making. Reduced vmPFC activity may explain why psychopathic individuals can know something is wrong without feeling that it’s wrong – the emotional signal doesn’t reach the decision-making process.

Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC). Involved in error monitoring and conflict detection. Reduced ACC activity may contribute to the lack of guilt or remorse – the error signal that should follow harmful actions doesn’t fire.

Connectivity. Perhaps more important than any single region is the connectivity between regions. Reduced connectivity between the amygdala and prefrontal cortex means that emotional signals don’t adequately influence cognitive processes. The person can think and feel, but the thinking and feeling don’t talk to each other.

The “Hot” Pattern: Hyperactivity

Not all psychopathy involves hypoactivity. Some individuals show the opposite pattern – hyperactive amygdala, hypothalamus, and periaqueductal gray (PAG, involved in defensive behaviors). These are the positive (red) correlations in the graph above.

This “hot” pattern is associated with:

Reactive aggression. Hair-trigger threat response; rage when provoked.

Hypervigilance. Constant scanning for danger.

Emotional intensity. Strong, rapid emotional reactions.

These individuals may still be called “psychopathic” because of their behavioral presentation (aggression, callousness in the moment), but the underlying mechanism is different. They’re not cold – they’re too hot, with reactive circuits that fire too readily.

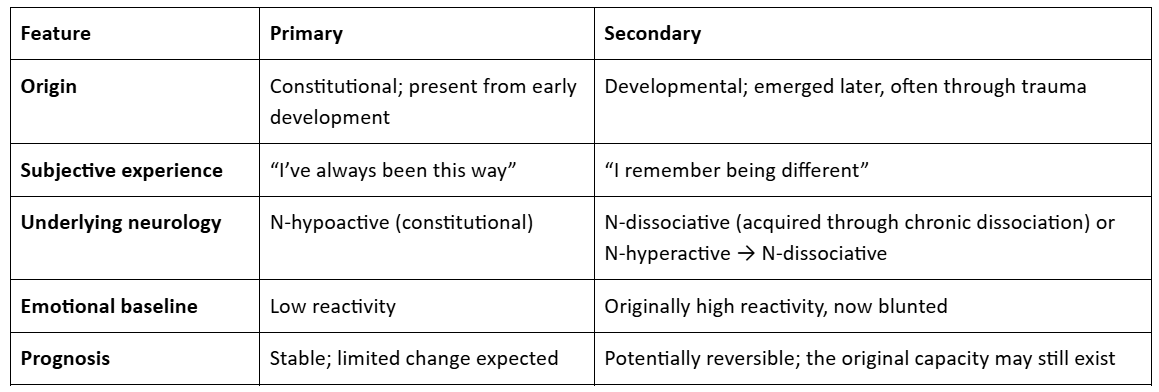

The Critical Distinction: Primary vs. Secondary

This brings us to an important distinction in understanding psychopathy: primary vs. secondary presentations.

Primary presentations reflect constitutional differences – the person was born with, or developed very early, a brain that processes emotions differently. They don’t remember being different. One of my friends fits this pattern: She has always had reduced empathy, high pain tolerance, and sadistic interests. Her father is similar. There’s no trauma, no “before” – this is just who she is.

Secondary presentations developed later, often as a defensive response to trauma. The person may have started with normal or even hyperactive emotional responses, but chronic trauma led to dissociative dampening. Their brain now looks hypoactive, but this is an adaptation, not a constitutional feature. Tiffany fits this pattern: She remembers being normal as a child, then adapted to severe adversity by developing sovereign traits. On good days, she can access empathy again. The original capacity wasn’t destroyed – it was suppressed.

Why This Distinction Matters

The primary/secondary distinction has enormous implications:

For prognosis. Primary presentations are likely to be stable. The person may learn to regulate behavior, develop values, develop selfhood, find prosocial outlets – but they’re unlikely to develop empathy they never had. Secondary presentations may be more changeable. If the dissociative dampening can be reversed, the original emotional capacity may re-emerge.

For intervention. Primary presentations can pursue values-based approaches, training prosocial habits, and finding harmless outlets for drives. Secondary presentations may benefit from moving to a safer environment, trauma processing, attachment repair, and interventions that help them feel safe enough to relax the dissociative defense.

For self-understanding. If you’re primary, trying to “develop empathy” may be frustrating and pointless; you’re better off doubling down on your strengths and forming a stable self. If you’re secondary, knowing that you weren’t always this way – and might not always be this way – can be important.

How to Assess: The Key Question

The simplest way to assess primary versus secondary is to ask:

“Were you always like this, or do you remember being different?”

If the person says they’ve always been this way – no memory of normal emotional responses, no “before” – that suggests primary. If they remember being different as a child – more emotional, more empathic, more afraid – that suggests secondary.

This isn’t a perfect test. Memory is fallible; some people may have been different without remembering it; some may confabulate memories of difference; some were vastly different but not in a more emotional/empathetic/fearful direction. But it’s a useful starting point.

Parsimonious N-Level Categories

Case Studies

Some of the profile terms will be clarified in later posts in the sequence.

Case A: The Lucky Primary

Profile. G-callous, N-hypoactive, E-I-secure (secure attachment), E-C-normal (normal childhood).

This person has constitutional psychopathic loading but developed in a supportive environment. They have always had reduced empathy and fear, high pain tolerance, and possibly sadistic interests. But they also have stable relationships, regulated behavior, and prosocial values.

They may not identify as having any disorder. They experience their differences as just “who I am” – perhaps useful in certain contexts (surgery, emergency response, high-stakes negotiation), perhaps something to manage in others (intimate relationships, parenting).

Implication. This person doesn’t need to “recover” from anything. They’re already functional. What they may benefit from is understanding – recognizing that their experience differs from others’, and developing strategies for contexts where their differences create friction.

Case B: The Primary Sovereign

Profile. G-minimal, N-hypoactive (secondary), E-I-avoidant (avoidant attachment), E-C-punitive (punitive parenting).

This person developed psychopathic features defensively. They don’t remember being different as a child because the neglect trauma happened too early. Perhaps their amygdala had already atrophied significantly by age 3 or memories before age 5 or so are missing because they changed too much. They now present as cold, calculating, and sadistic.

But the original capacity exists to some extent. On good days, they may experience flashes of empathy or guilt. They are not complete strangers to fear. They may have stable attachments to a few people (children, specific partners) even while being callous toward others.

Implication. This person may be able to recover – not necessarily to become “normal,” but to regain some access to emotional capacities that were suppressed. This requires safety, stable attachment, and possibly trauma processing. It’s a multi-year-long journey and a different one from primary presentations.

Case C: The Secondary Sovereign

Profile. G-minimal, N-hyperactive (secondary), E-I-disorganized (disorganized attachment), E-C-punitive (punitive parenting), D-max-avoidant (pervasive avoidant attachment).

This person also developed psychopathic features defensively. They remember being different as a child – more emotional, more afraid, more connected. Severe trauma led them to develop dissociative defenses, and their emotional responses became blunted, perhaps from one day to the next as they gave up on parents, friends, society, and humanity. They now present as cold, calculating, sadistic, thrill-seeking.

But the original capacity exists. On good days, they may experience flashes of empathy or guilt. They may have stable attachments to a few people (children, specific partners) even while being callous toward others.

Implication. This person may be able to recover, even suddenly – not to become “normal,” but more likely to enter into a state of borderline personality disorder due to their disorganized attachment, for which there are many treatments like Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) and Mentalization-Based Treatment (MBT).

Case D: The Reactive Chaotic

Profile. G-reactive + G-impulsive, N-hyperactive, E-I-disorganized (disorganized attachment), E-C-violent (chaotic childhood), D-autonomic.

This person has high emotional reactivity that never got regulated. They experience intense emotions – especially anger – and act on them impulsively, especially in response to perceived infringements on their autonomy. Their violence is “hot” (reactive rage) rather than “cold” (instrumental calculation).

They may be called “psychopathic” because of their behavior, but the underlying mechanism is different from classic psychopathy. They’re not underreactive; they’re overreactive. Their problem is dysregulation, not absence of feeling. They might even experience guilt once enough time has passed since the triggering event.

Implication. This person needs stabilization and regulation skills before anything else. Approaches like Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) may be helpful. The goal is not to develop emotions (they have plenty) but to regulate them.

The Substrate Is Not the Person

A crucial point: The G and N levels describe the substrate – the biological foundation on which the person developed. But the substrate doesn’t determine the person.

The same N-hypoactive pattern can produce:

A functional surgeon who saves lives

A successful CEO who builds companies

A serial killer who destroys lives

What makes the difference is everything else: The environment (E), the psychological structures that developed (D), the behaviors that became habitual (B), and how the person understands themselves (A).

This is why we need a multi-level framework. Knowing someone’s substrate is useful, but it’s not sufficient. To understand them fully, we need to know the whole profile.

Summary

G-level (genetic). Psychopathy has a heritable component, but it’s polygenic and probabilistic. Key loadings include G-callous (reduced empathy/fear), G-reactive (emotional reactivity), and G-impulsive (disinhibition).

N-level (neurological). The classic finding is amygdala hypoactivity, but there’s also a hyperactive pattern (reactive aggression) and a dissociative pattern (secondary blunting). The primary/secondary distinction – “always this way” versus “remember being different” – has major implications for prognosis and intervention.

The substrate is not destiny. Biology creates predispositions, not determinations. The same substrate can produce very different outcomes depending on environment and development.

Next: The Shaping

The next article explores the E level – how environment and development shape the expression of the biological substrate. Why does the same genetic loading produce a functional person in one context and a criminal in another? What types of adversity lead to what outcomes?