Psychopathy: The Mechanics

How empathy fails: a process model

This is the fifth article in a series on understanding psychopathy. Previous articles covered the framework, biology, environment, and psychological structure. This article explores the different ways empathy can fail to influence behavior – because understanding the mechanism matters for understanding the person.

Introduction

“Lack of empathy” is a core feature of psychopathy, but the phrase hides enormous variation. Someone who can’t perceive distress is different from someone who perceives it but feels nothing. Someone who feels distress but doesn’t care is different from someone who cares but acts anyway because rage overwhelms.

This article presents empathy as a pipeline with multiple stages, each of which can fail independently. Understanding where someone’s empathy fails helps predict their behavior and suggests different intervention approaches.

I’ll call this pipeline C for connective or communicative, because it comprises more aspects than just the cognitive (simulation) and affective components that are commonly associated with empathy.

Empathetic Connection as a Pipeline

Connection isn’t one thing – it’s a sequence of processes:

PERCEPTION → SIMULATION → AFFECT → MOTIVATION → BEHAVIOR

Each stage can fail independently:

Perception. Noticing and recognizing the other’s state.

Simulation. Modeling what the other is experiencing.

Affect. Generating an emotional response to that model.

Motivation. Caring about the emotional response – attaching moral weight.

Behavior. Translating care into action (or restraint).

Books like Against Empathy make the case that affective empathy is often a bad guide to moral decision marking. I agree. The affective component can feel very lovely and connecting and it can be motivating when there are competing considerations – for good or ill.

As such, what is important in this pipeline is that processes of perception and simulation eventually lead to behavior (which requires motivation). Some of my friends can do that reliably without the affect component, and in many everyday and life decisions – such as where to donate – I try to avoid getting biased by affective responses.

The resulting pipeline goes:

PERCEPTION → SIMULATION → MOTIVATION → BEHAVIOR

Different failures at different stages produce different presentations.

Stage 1: Perception Failures

The other’s distress isn’t registered at all.

C-P-inattention: Not Noticing

Not attending to distress cues. Distracted, focused elsewhere, not looking.

This is the default in our society. Millions of humans dying of preventable diseases, trillions of animals suffering in factory farms, sextillions of animals living in abject conditions in the wild, many more throughout the future. Most people don’t realize it in the first place.

C-P-aversion: Flinching Away

Actively avoiding perceiving the other’s state. Like C-P-inattention but with a defensive purpose behind it. Some pwNPD flinch away from mentalizing people they hurt – they could perceive their distress, but doing so would produce an empathetic response they don’t want to feel. So they avert their gaze.

This suggests the empathy capacity is present but defended against.

This is the default in our society among people who do realize how much suffering there is. They look away.

C-P-non-recognition: Not Recognizing

Sees the cues but doesn’t recognize them as distress. May be related to alexithymia (difficulty identifying emotions) or the difficulty reading neurotypical social cues that autistic people run into. The signal is there, but it’s not decoded.

Most people struggle with this when interpreting the distress cues of fish and most invertebrates because they are too different.

C-P-objectification: Seeing Object, Not Person

Deliberately or habitually classifying the target as an object rather than an agent with experiences.

One example from my own experience: When a friend gets a minor injury and I need to help rather than pass out from empathic distress, I see them as “a damaged object that needs repair” rather than “a person in pain.” This is strategic objectification – useful in the moment, then released.

For some people, this is the default mode. Others are objects, resources, obstacles – not minds with experiences. This bypasses the empathy pipeline entirely, so it’s also useful for empathizing with sadism – i.e. behave sadistically toward literal objects to experience what it is like.

I imagine that most people have an objectified relationship towards most invertebrates, excluding large ones like octopuses. When an animal dies, it’s telling whether people react with indifference, appetite, or wanting to bury the body.

Stage 2: Simulation Failures

These come in two flavors: mentalizing the other and mentalizing the self – or failing to.

C-S-no-pain: Can’t Imagine Pain

If your own pain perception is blunted, you may lack the experiential substrate to simulate others’ pain accurately.

One friend said, “They’re just nociceptive stimuli. I can just ignore them.” If that’s their relationship to their own pain, how would they simulate the agony of someone else’s injury? (Then again I find it more likely that they noticed a lack of fear of pain and confabulated a reason for it when really the reason is that they don’t have a fear response.)

This is not callousness in the moral sense – it’s a genuine simulation deficit. They’re not choosing to ignore your pain; they can’t imagine it because they don’t experience pain that way themselves.

C-S-no-self: Can’t Imagine Attacks on Selfhood

M.E. Thomas (D-anatta) describes having no selfhood to attack. Physical pain she can imagine, somewhat. But humiliation? Self-image injury? These don’t compute because she doesn’t have the internal referent. Or they didn’t. She’s trained her selfhood over the past ten years and how has a better idea of what it’s like also introspectively.

If you have no self, you can’t simulate what it feels like to have your self attacked. This means certain kinds of harm – infractions of autonomy, reputational damage, humiliation, self-image injury – may be genuinely incomprehensible, not merely disregarded. Autonomy is a particularly interesting case because if someone has no self whose autonomy to value, how would they realize that there is one person who they can manipulate (themselves) but not anyone else, unless they’ll make them angry. It’ll seem like a weird and arbitrary social mechanism.

C-S-no-shame: Can’t Imagine the Feeling of Shame

Some people don’t have the feeling of shame. Perhaps they don’t recognize the idea of being part of a social group, and hence motions that these groups make to use shame against them end up being just empty motions.

Such a person might imitate these motions to express their disapproval or persuade someone to do something, but they don’t realize that for the other person, these motions are deep cuts to their self concept.

Along the same lines, it makes sense to recognize simulation failures like C-S-no-guilt (which might cause someone to use guilting motions on another which they would scruple to do if they knew what it feels like) or C-S-no-fear (which might cause someone to act erratically or threatening, which they would try to control if they knew what the fear feels like that they instill).

C-S-projection: Simulating the Wrong State

Simulating what you would feel rather than what they feel. A masochist might project their own relationship to pain onto a victim, imagining the victim enjoys it. A stoic might project their own equanimity, underestimating the victim’s distress. A person who enjoys learning about personality disorders might project their enthusiasm, underestimating the victim’s annoyance at listening to nothing else for years.

C-S-underestimation: Simulating But Minimizing

The simulation happens but the intensity is underestimated. “It’s not that bad.” “They’ll get over it.” “Pain is just a signal.”

This may be related to C-S-no-[substrate] – e.g., if you don’t experience much pain yourself, you may simulate others’ pain as similarly mild.

C-S-hypermentalizing: Constructing False Attributions

Simulation happens but produces inaccurate, self-serving results. “They actually like it.” “They’re not really hurt.” “They’re exaggerating for attention.” “That’s their only purpose in life.” The model is constructed, but it’s wrong – and wrong in a defensive direction.

C-S-impulsive: Acts Before Reflection

The action happens before the empathic/moral processing can complete. The person might have arrived at a different resulting action if they’d paused – but they didn’t pause.

C-S-prospective: Can’t Anticipate Future Guilt

The person can feel guilt retrospectively, but not prospectively. In the moment of action, they can’t access the knowledge that they’ll feel terrible later.

“She gets angry, does bad stuff, and then regrets it. But she can’t anticipate that she’ll feel that way.”

This is state-dependent access – the guilt is real but only accessible in a different state. This may be related to N-disconnected.

C-S-state-dependent: Empathy Only in Certain States

Mentalizing is available in some states (calm, secure) but not others (angry, dissociated). The capacity exists but isn’t consistently accessible.

C-S-temporal-discounting: Future Doesn’t Weigh

Future guilt is acknowledged but heavily discounted. “I’ll feel bad later, but I don’t care now.” The temporal distance makes the future suffering abstract and powerless.

C-S-depleted: Too Exhausted for Restraint

The theory of ego depletion avers that self-control is a limited resource. If so, a person would mentalize comprehensively if they had the energy, but they’re too tired.

C-S-intoxicated: Chemically Disinhibited

Alcohol or other substances interfere with proper mentalizing.

C-S-retroactive: Rewriting to Prevent Guilt

After the action, the memory is rewritten to prevent guilt. “They deserved it.” “It wasn’t that bad.” “They got over it.” This prevents guilt from forming even when it otherwise would – and prevents learning from the experience for the next round of mentalizing.

Stage 3: Affective Failures

Simulation doesn’t produce an emotional response.

C-A-blunted: Weak or Absent Affect

The simulation is accurate, but it doesn’t produce an emotional response. You understand they’re in pain, but you don’t feel anything about it. This is the classic N-hypoactive pattern – the amygdala and insula don’t fire, so there’s no affective resonance.

This is also something that affects most people when it comes to the suffering of invertebrates and fish.

C-A-suppressed: Affect Generated But Suppressed

The emotional response is generated but actively suppressed. This is different from C-A-blunted – the affect is there, but defenses keep it out of awareness. Friends of mine describe practices of automatic or habitual rationalizing and compartmentalizing to not feel bad. The affect would be there if they let it.

C-A-inverted: Pain Produces Pleasure

The simulation is accurate, and an affect is generated – but it’s positive. The other’s pain produces pleasure. This is sadism in the true sense: Inverted empathic affect. It might translate to pain beyond nociception, e.g., humiliation.

C-A-override: Stronger Affect Drowns Empathy

The empathic affect is generated, but it’s overwhelmed by a stronger affect – rage, fear, desire, domination. The person does feel the other’s distress, but they feel their own rage more, and the rage wins. The pain might even enhance a competing feeling of domination.

One friend of mine gets angry, does things that are in violation of her values, and then regrets it and feels remorse afterwards. But she can’t anticipate that she’ll feel it when she does those things. At that time it feels perfectly justified.

This is not absence of empathy – it’s empathy overwhelmed by rage, with retrospective access.

C-A-redirected: Empathic Distress Becomes Anger

The empathic distress is generated, but instead of producing compassion, it produces anger at the person causing the distress – sometimes the victim themselves. “Stop making me feel bad about you!”

This can lead to victim-blaming and avoidance: The distress is aversive, so the source of distress (the suffering person) becomes aversive. Specifically the patterns that I’ve identified are resentment and control-seeking: You feel wronged because someone is asking you for a kind of accountability that has never been granted you in the past; you’ve internalized that you mustn’t show the emotions the person is showing, so you feel like they’re violating your conduct norms; or you’re used to getting endlessly attacked for your mistakes, so you try to never admit to any.

C-A-anhedonia: Sadism as One of Few Pleasures

Some people have generally blunted pleasure (anhedonia), but sadism is one of the few things that still produces feeling. The sadism isn’t about the victim per se – it’s about accessing any feeling at all. Perhaps it’s not even particularly pleasurable, but it is intense, it is a reprieve from the nothingness.

This may relate to the “void” that some psychopathic presentations describe – the emptiness that gets filled with substances, thrills, or sadism.

Stage 4: Motivational Failures

Affect is present but doesn’t translate to moral concern.

C-M-amoral: No Moral Weight Attached

The empathic affect is present – you feel something when you see their pain – but it doesn’t connect to moral value. It’s just information, not a reason to act or refrain.

Here it’s important to distinguish descriptive and metaethical moral realism. (I find the first fairly uninteresting but reject the second, not on the grounds of moral realism but on the grounds of something like metaethical expressivism and a resulting global market of moral preferences.)

Descriptive Moral Relativism (DMR). As a matter of empirical fact, there are deep and widespread moral disagreements across different societies, and these disagreements are much more significant than whatever agreements there may be.

Metaethical Moral Relativism (MMR). The truth or falsity of moral judgments, or their justification, is not absolute or universal, but is relative to the traditions, convictions, or practices of a group of persons.

But some people do subscribe to something like MMR, in which case they attach or don’t attach a moral weight to the same states depending on who is affected by them, where, or in which context.

This is a bit of a catch all for amoral non-responses that are not covered with more specificity below.

C-M-dehumanization: They Don’t Count

The target is classified as not deserving moral concern. “They’re not really people.”

C-M-justification: Feels Justified

Moral concern is overridden by felt justification. “They deserved it.” “They started it.” “It was self-defense.” The empathic information is present, the moral weight is attached, but the justification outweighs it.

This is C-A-override’s sibling: Not just that an emotion overwhelms another, but that it comes with a notion that it feels justified, so the action feels right.

C-M-ideological: For the Greater Good

Higher value overrides moral concern for the individual. “I’m saving the world.” “The ends justify the means.” “One death to prevent a million.”

Ozymandias from Watchmen is the extreme example – killing millions for calculated peace. The empathic information is present, the moral weight is attached (he knows it’s terrible), but the utilitarian calculation overrides.

C-M-competing: Other Desires Outweigh

Moral concern is present but weaker than other motivations – appetite, greed, revenge, lust, ambition. The person knows it’s wrong and feels it’s wrong, but does it anyway because they want to.

C-M-licensing: Earned the Right

“I’ve been good, so I can be bad now.” Moral accounting that permits occasional violations.

C-M-diffusion: Not My Responsibility

Bystander effect logic. “Others could help.” “It’s not my job.” Moral concern is present but responsibility is diffused.

C-M-identity: Empathy Threatens Self-Concept

Acknowledging the empathic information would threaten the self-concept. For sovereigns, admitting empathy might feel like weakness. For some ideologies, empathizing with the “enemy” is betrayal. So the empathic information is dismissed or suppressed.

Stage 5: Behavioral Failures

Behaviors are not sufficiently externally constrained.

C-B-others: Interpersonal Power Differentials

If the interpersonal power differential is minimal, the other person can effectively constrain one’s behaviors. If not, the behavior can’t be effectively constrained at this level, be it in the moment or through feedback to prevent future iterations.

Sources of power differentials: avoidant attachment, physical strength, life experience, martial arts experience, weapons, positions of institutional power, financial power, blackmail material, etc.

C-B-institutions: Institutional Power Differentials

In extreme cases, someone is above the law so that there’s not only an interpersonal power differential but a universal one, the lack of feedback that many dictators suffer from and that, e.g., caused Putin to underestimate the costs of the war on Ukraine.

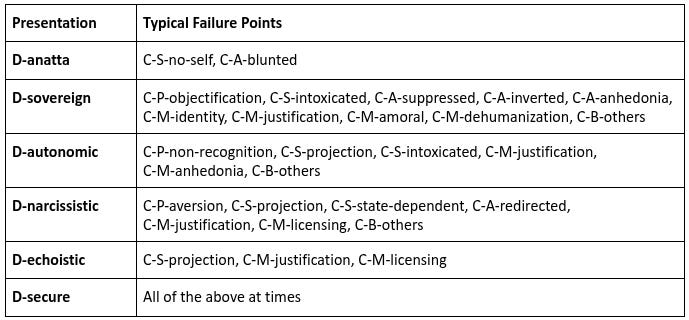

Mapping Failure Points to Presentations

Different presentations tend to fail at different points. Understanding where the failure is helps target intervention – if there is one.

Why This Matters

For self-understanding. If you know your empathy fails at the simulation stage (you can’t imagine their pain because you don’t experience pain that way), that’s different from failing at the motivation stage (you feel it but don’t care). Understanding your mechanism helps you work with it.

For predicting behavior. Different failure points predict different behaviors. C-A-override (rage overwhelms) predicts reactive violence; C-A-blunted (no affect) predicts cold instrumentality; C-M-justification predicts violence framed as deserved.

For intervention. Some failure points are more modifiable than others. C-B-impulsive might be helped by slowing down, creating pause, like with the DBT STOP skill. C-A-suppressed might be helped by creating safety that allows the affect to emerge. C-A-blunted is probably stable.

For others’ self-protection. If you know someone’s failure point, you know how to protect yourself. C-A-override people are dangerous when triggered; C-A-blunted people are dangerous when you have something they want; C-M-justification people are dangerous when they feel you’ve wronged them.

Next: The Types

The next article presents the archetypal clusters – common profiles that tend to co-occur. Rather than abstract dimensions, we’ll look at recognizable types that readers may identify with.

Hey, great read as always. This pipelin model for empathy is super insightful, especially from a CS perspective. It really helps clarify that 'lack of empathy' isn't a monolit, but a system failure with distinct points of breakage. Makes you think about how complex even basic human connection is and what it means for AI.