When “Sorry” is Hard: Mapping the Boundary Struggle in NPD

Understanding the patterns that make boundaries and accountability feel impossible – and what lies beneath them.

Why It Matters

If you’re reading this as someone with narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) working on your recovery, you’ve probably noticed a painful pattern: Moments when someone you care about sets a boundary or asks for accountability, and something in you can’t meet them there. You might deny, deflect, attack, or shut down – even when part of you knows you’ve caused harm.

You’re not broken or incapable of healthy relationships. These are protective patterns – strategies your psyche developed to survive experiences that were genuinely threatening to your sense of self.

But here’s the hard truth: While these patterns made sense when they formed, they’re often the most relationship-damaging aspect of NPD. Partners, friends, and family members can weather a lot, but when someone can’t acknowledge harm or respect boundaries, trust erodes. Relationships that could have survived imperfection often can’t survive the inability to repair.

The good news: These patterns aren’t monolithic. Different people struggle with boundaries for different underlying reasons, and understanding your particular pattern is the first step toward working with it rather than being controlled by it.

This article offers a map – not a diagnosis, but a framework for self-understanding. You may recognize yourself in one pattern or several. The goal isn’t to add another layer of shame, but to make the invisible visible, so you can start to catch these patterns in action and, eventually, choose differently. That is something to be proud of.

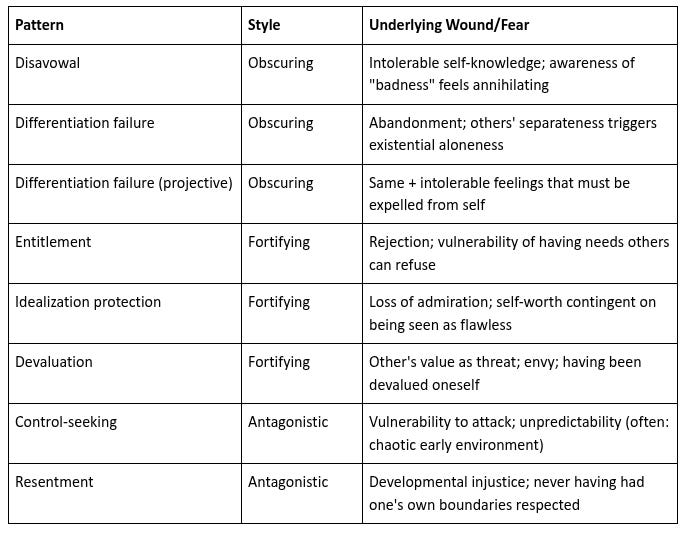

The Patterns at a Glance

I’ve identified eight distinct patterns that interfere with boundary respect and accountability. Each falls into one of three styles based on how the defense operates, and each is rooted in a particular underlying wound or fear.

Understanding the Taxonomy

Three Defense Styles

Obscuring defenses work by preventing accurate perception. You don’t see clearly – either yourself, the other person, or what actually happened. These patterns aren’t willful distortion; they operate before conscious awareness. Sometimes you’ll see glimpses of other framings before the defenses shut them down. Sometimes the memories come back when you’re in a different mood. In your recovery, you’ll start to remember them dimly.

Fortifying defenses work by protecting the environment that you need in order to maintain your self-image. These can be unconscious defenses too. You try to find some reframing of reality that protects you from devastating feelings of dependency or inadequacy. The goal is less to hide the reality from you than it is to maintain the scaffolds you’ve build around you to survive.

Antagonistic defenses work by fighting. Rather than not-seeing or wall-building, you’re opposing and defending against the other person. These patterns often feel more ego-syntonic – you’re aware you’re fighting, and it feels justified or like you don’t have a choice.

Two Temporal Modes

Each pattern can manifest in proactive or reactive form:

Proactive. The defense is always-on or anticipatory. You’re scanning for threats, prefiltering information, or rigidly positioning yourself in certain ways. This can manifest as a general tendency toward avoidant attachment – claiming that you don’t need the other, and that they should rather leave you alone than ask for accountability, even when deep down you actually value the relationship but can’t admit it. It might also manifest as general avoidance in many areas of life, a constant narrative of your pretend reasons for any behaviors, or a compulsion to only interact with people you can control.

Reactive. The defense activates in response to a specific trigger – a criticism, a boundary, a confrontation. In this case you’re usually clear-minded, but when your amygdala detects a threat (such as someone asking you for an apology), you switch into a threat response state – fight, flight, freeze, fawn, or flop – like you’re in mortal danger, which makes it hard to think clearly and can interfere with memory formation too.

Most people have a mix, but noticing your dominant mode can help you catch patterns earlier.

The Patterns

Disavowal

Always one mistake away from death and damnation.

What it is. The inability to acknowledge having transgressed. When you’re confronted with signs of having made a mistake, the truth is unbearable. Either you’ve preemptively convinced yourself of a reframing or pretext or altogether different narrative, or your threat system reflexively devises one on the spot. A question of connection or relating with another is recast as a question of right and wrong.

The underlying wound. At the core is deep shame. Trauma that has made you feel like you’re never enough, like you’re always at the edge of society or breakup, one mistake away from humiliation or death. The shame is no mere embarrassment – it’s annihilating, identity-destroying. Disavowal isn’t about avoiding accountability; it’s about avoiding psychological death. Somewhere along the way, you learned that being bad or weak or fallible meant being nothing. Perfectionism to the point of self-delusion seemed like the only way out.

How it feels from the inside. Often, there’s no felt sense of lying. The alternative version of events feels true. Either because it is (through cherry-picking facts or framings) or because you’ve meticulously rewritten your memories. When someone insists you did something hurtful, it may feel like a bizarre accusation that doesn’t match your experience at all. Or there’s a flash of knowing, immediately followed by mental static – the knowledge is there and then it’s not there. Sometimes there’s a dreamlike quality: “Maybe something happened, but it feels distant, unreal, like it was someone else.”

Proactive form. A rigid “I’m a good person” identity (or insert a more precise attribute for “good”) that prefilters all contradictory information. You may have a strong internal narrative about your values and intentions that automatically reframes questionable behavior. Shame-inducing information doesn’t land because the identity structure rejects it before it registers.

Reactive form. When directly confronted, your regular consciousness turns off and you launch into an attack-type threat response, as if a tiger jumped out of the bushes and you’re fighting for your life. Some Lovecraftian god of chaos throws massive numbers of excuses and counterattacks your way for you to pick from. You find yourself arguing about the facts of what occurred rather than empathizing with the impact on the other person.

Toward recovery. The path through disavowal begins with building tolerance for shame – perhaps not eliminating it at first, but learning that it won’t destroy you. Self-compassion practices are essential: Can you hold “I did something hurtful” alongside “I’m still worthy of love”? Recording yourself during difficult conversations (with consent) or keeping a detailed journal can help you catch the gap between what happened and what you remember. In therapy, EMDR can process the original traumas that made shame feel annihilating. Mindfulness meditation trains you to notice that flash of knowing before the static descends – that’s your window. Shadow work helps you integrate the “bad” parts you’ve been fleeing. The goal isn’t to become someone who never errs, but someone who can say “I hurt you, and I’m sorry” without dying inside. Or even while loving every bit of the messiness that connects us all.

Differentiation Failure

When boundaries feel like they’re harvesting your organs.

What it is. Difficulty experiencing others as truly separate beings with valid, independent needs. When your partner expresses a need that conflicts with yours, or sets a boundary, it doesn’t compute. Their separateness registers as abandonment, betrayal, or as if they’re ripping out a part of you rather than as a normal feature of relating.

The underlying wound. This pattern often develops when early attachment was either enmeshed (no permission to be separate) or chaotic (separateness meant abandonment). The wound is existential aloneness – a terror that if others are truly separate from you, with their own centers of gravity, you’ll be left alone, incomplete, or vanish. Secure attachment allows children to internalize “I can be separate and still complete and connected.” Without that, you mistake the merging that happens when someone completes you for connection, and actual connection is unsatisfying because it doesn’t protect you from the knowledge of your own incompleteness.

How it feels from the inside. When someone close to you says “no” or expresses a different need, it can feel viscerally wrong – as if they’re stealing from you, harvesting your organs. There’s genuine shock and confusion: “Why would you do this to me?” Other people’s independent actions feel personal to you. The idea that they have their own inner world with its own logic may be intellectually available but doesn’t feel emotionally real.

Proactive form. Chronically experiencing others as extensions of yourself – satellites orbiting your sun. Their function is to meet needs, reflect value, provide support. Their separateness simply doesn’t register; you may be surprised when reminded they have constraints, preferences, or limitations you weren’t aware of.

Reactive form. When someone refuses a favor, sets a boundary, or expresses an independent need, there’s genuine hurt and betrayal: “Why are you doing this to me?” The boundary feels like they’re cutting out a piece of you rather than a neutral expression of their needs.

Toward recovery. Recovery from differentiation failure is fundamentally about building the felt sense that others exist as complete beings even when they’re not there for you, and that connection can survive separateness. Reparenting work in therapy helps internalize the secure attachment you missed. Mentalization-based treatment (MBT) trains you to genuinely wonder “What might they be experiencing right now?” in a flexible way that is open to collaborative exploration and multiple hypotheses. Authentic relating and circling practices offer structured ways to encounter others’ genuine otherness in a safe container. Mindfulness meditation builds capacity to sit with the incompleteness that separateness triggers, discovering it’s survivable. The shift you’re working toward: from “their boundary is abandonment or robbery” to “their boundary is information about them, and we’re still connected.”

Differentiation Failure (Projective)

The empath delusion.

What it is. A more severe variant where your own intolerable feelings or motives are experienced as coming from the other person. This isn’t strategic blame-shifting; it’s a genuine perceptual distortion where what’s inside you appears to be outside you.

The underlying wound. This includes everything from basic differentiation failure, plus an additional layer: certain feelings or parts of yourself are so intolerable that they can’t be owned. They must be evacuated, expelled, placed outside. This often develops when certain emotions were forbidden or punished in childhood – rage, selfishness, neediness, interdependence. These parts didn’t disappear; they went into exile, and now they can only be experienced as belonging to others. The wound is: “Parts of me are so unacceptable that I can’t know they’re mine.”

How it feels from the inside. You genuinely experience the other person as doing what you’re actually doing. If you’re angry, they seem aggressive. If you’re withdrawing, they seem cold. The strangler who screams “Why are you strangling me?” isn’t lying – in their experience, they are as much victim as they are themselves. At less extreme levels: “Why are you so hostile?” when you’re the hostile one, with complete sincerity.

Proactive form. Chronically attributing your own states and motives to others. You may be known for “reading” people in ways that reveal more about your own psychology than theirs.

Reactive form. In conflict, your own aggression, manipulation, or selfishness is experienced as emanating from the other person. You feel victimized by the very thing you’re doing.

Toward recovery. The projective variant requires reclaiming the exiled parts of yourself. Shadow work is central: What feelings were forbidden in your childhood? Can you begin to own rage, neediness, selfishness as yours rather than seeing them only in others? Journaling after conflicts – “What was I feeling? What was I doing?” – helps build self-knowledge. Mentalization-Based Treatment (MBT) trains you to hold multiple perspectives simultaneously: “I experience them as hostile, and I might be projecting.” Circling and authentic relating provide feedback from others about how you’re actually showing up, which can be reality-testing for your projections. In therapy, the relationship itself becomes a laboratory for catching projection in action. Ayahuasca and other psychedelic-assisted therapies, in appropriate settings, can facilitate encounters with disowned parts. The goal: Welcoming home the exiled feelings so they don’t have to live in others anymore.

Entitlement

When desperate self-sufficiency and rejection sensitivity collide.

What it is. An unconscious assumption that things are owed rather than requested. This isn’t arrogance in the simple sense – it’s a defense against the vulnerability of having needs that others can refuse. By assuming entitlement, you never have to feel the dependency, submission, indignity, or risk the rejection inherent in asking.

The underlying wound. Underneath entitlement is often a deep terror of rejection or dependency and what they imply about one’s relative status. To ask for something is to admit you need it, to reveal vulnerability, and to give the other person power to say no. If you grew up with needs that were ignored, mocked, or weaponized, asking may have become unbearable. Entitlement is a workaround: if it’s owed, you don’t have to ask, you don’t have to be vulnerable, and refusal becomes their moral failure rather than your rejection. The wound is: “My needs make me vulnerable, and vulnerability is dangerous.”

How it feels from the inside. You don’t feel entitled in the entitled sense – it just seems obvious that certain things should happen. When they don’t, it feels like injustice rather than disappointment. There’s a qualitative difference between “I’m sad you didn’t do X” and “How could you not do X?” – the latter feels righteous, wounded, betrayed. Making explicit requests feels strange, unnecessary, or even humiliating.

Proactive form. Assumptions about what others will do for you operate invisibly. You don’t ask because asking would imply it wasn’t already owed. You may be surprised when others describe you as demanding, because from inside, you weren’t demanding – you were expecting normal treatment.

Reactive form. When an expectation is unmet, the response is anger and betrayal, not disappointment. This feels like a response to genuine wrongdoing. The hurt is real; what’s obscured is that you never communicated the expectation, or that the other person had any right to refuse.

Toward recovery. Entitlement dissolves when asking becomes safe. Start small: Practice making explicit requests where the stakes are low. DBT’s interpersonal effectiveness skills (DEAR MAN) provide scripts for asking that feel less vulnerable. Self-compassion work helps you befriend the dependency you’ve been hiding from – needs are human, not shameful. Exposure therapy principles apply: gradually facing small rejections teaches your nervous system that “no” isn’t annihilation. Reparenting yourself means learning to meet some of your own needs, reducing the desperate dependency on others. In therapy, explore the original wounds around asking: when did it become dangerous? Journaling can track the gap between “what I expected” and “what I communicated.” The shift: from silent expectation and righteous rage to clear requests and disappointment you can survive.

Idealization Protection

Why impersonate a priest when you can perfectly impersonate the pope.

What it is. Protecting the idealized self-image that generates admiration (and thus self-esteem). Flaws must be hidden, denied, or explained away because being seen as imperfect threatens your source of worth. It’s the fortifying flip-side of disavowal.

The underlying wound. This pattern often develops when love and approval were conditional on performance or appearance. You learned that you were valued for what you achieved, how you looked, how you made others feel – not for who you were. The idealized image became load-bearing: without it, there’s nothing. The wound is a missing floor – no stable sense of worth that exists independent of others’ admiration. Imperfection doesn’t just mean you made a mistake; it means a threat to the very source of your worth. The desperation to maintain the image is proportional to the void beneath it.

How it feels from the inside. There’s a desperate, urgent quality to keeping up appearances – though it may be so automatic you don’t notice it as effort. When a flaw is exposed, there’s panic, followed by rapid narrative management: minimizing, recontextualizing, or dissociating. Perhaps you know the flaw is real, but admitting it feels like it would be catastrophic – far worse than the objective situation warrants.

Proactive form. Meticulous image curation. Avoiding situations where imperfection might show. Controlling what others see. This may be exhausting, but it’s load-bearing – without it, you fear the whole structure would collapse.

Reactive form. When a flaw is exposed despite your efforts, immediate damage control, alternative explanations, or sometimes genuine dissociation where the event becomes hazy and unreal.

Toward recovery. The cure for idealization protection is building a floor – a sense of worth that doesn’t depend on admiration. Reparenting in therapy is key. It offers the experience of being valued for who you are, not just what you achieve. Mentalization-Based Treatment (MBT) can train you to recognize in other when they’re read to love a flawed you more than a perfect you. Self-compassion (Kristin Neff’s work) trains unconditional warmth toward yourself. Start intentionally revealing small imperfections in safe relationships – exposure therapy for the fear of being seen as flawed. Mindfulness helps you notice the panic when a flaw surfaces, creating space before the damage-control reflex kicks in. The goal isn’t to stop caring about excellence, but to survive being seen as human.

Devaluation

The source of contempt, dismissiveness, pity, and of all those people who don’t get it.

What it is. Diminishing the other person’s worth, value, or standing – making their needs, feelings, or boundaries not matter by making them not matter. This protects against envy, against others having power over you, and often against your own history of being devalued. It’s the flip-side of idealization.

The underlying wound. Devaluation often serves multiple functions. It can defend against envy – if they’re lesser, their successes don’t threaten you. It can protect against dependency – if they’re not that important, you don’t need them. And frequently, it re-enacts what was done to you: if you were chronically devalued, diminished, or treated as less-than, you may have internalized that someone in every relationship has to be “less.” Making it them instead of you feels like winning or survival.

How it feels from the inside. The other person seems genuinely less important, less competent, less reasonable, or less deserving. Their boundary feels ridiculous because they’re being ridiculous. Their hurt feelings are them being “oversensitive,” and you can dismiss them anyway as a them problem. This isn’t strategic – in the moment, you really see them as lesser, inferior, irrelevant. There may be contempt, dismissiveness, pity, or a sense of being surrounded by people who just don’t get it. Sometimes, underneath, there’s a flicker of envy or threat that the devaluation is managing.

Proactive form. Chronically positioning others as lesser. You may have a taxonomy of people’s inadequacies that feels like clear-eyed assessment rather than defense. Others’ boundaries or needs don’t warrant respect because they don’t warrant respect.

Reactive form. When someone sets a boundary or challenges you, they’re immediately reframed as ridiculous, oversensitive, controlling, pitiable, or otherwise not worth taking seriously.

Toward recovery. Devaluation often protects against envy, dependency, and acknowledging flaws – so working with those is key. Shadow work helps you recognize the qualities you’re diminishing in others as things you might fear or want in yourself. Alternately, the previous two sections can be helpful because devaluation is just the flip side of idealization, so as the need to idealize fades away, so does the need to devalue. Mentalization-Based Treatment (MBT) trains curiosity about others’ inner worlds, which is incompatible with dismissing them as lesser. Gratitude exercises specifically for the people you tend to devalue can also rewire the reflex. If you were chronically devalued yourself, grief work and trauma processing (EMDR, somatic therapies) can help you stop perpetuating what was done to you. Circling and authentic relating put you in contact with others’ full humanity in ways that make devaluation harder to maintain. The shift: from “they’re lesser” to “they’re different, and their perspective is real.”

Control-Seeking

Someone feels hurt. They’ll seek revenge. All hands to battle stations!

What it is. Perceiving criticism or boundary-setting as an attack and responding by seizing control of the interaction. This often develops in chaotic or abusive early environments where the best defense was a strong offence.

The underlying wound. If you grew up in an unpredictable or dangerous environment – where criticism preceded punishment, where vulnerability was exploited, where you never knew when the next blow (physical or emotional) would land – your nervous system learned that safety means control. Letting someone else set the terms of an interaction, letting a criticism land, letting yourself be accountable – all of these feel like letting your guard down in enemy territory. The wound is: “I was blindsided and hurt when I was vulnerable, so I must never be vulnerable again.” Control isn’t about dominance; it’s about survival.

How it feels from the inside. When someone expresses hurt or sets a boundary, it feels like the opening move in an attack. Your nervous system may go into fight mode before you’ve consciously processed what’s happening. There’s a sense that you have to get ahead of this – that if you let them finish, if you let the criticism land, something terrible will happen. It feels like survival, not strategy.

Proactive form. Constant vigilance. Scanning for threats. Preemptive strikes – attacking potential criticism before it can be voiced. “The best defense is a good offence.” You may have developed sophisticated skills at steering conversations away from dangerous territory.

Reactive form. When criticized, immediate counterattack: “What about when you…?” Overwhelming the other with grievances. DARVO (Deny, Attack, Reverse Victim and Offender). The goal, often unconscious, is to end the interaction on your terms, with your narrative in control.

Toward recovery. Control-seeking is fundamentally a nervous system issue – your body learned that vulnerability means danger. Trauma processing (EMDR, IFS, somatic experiencing) can discharge the original survival responses so they’re not constantly online. The distress tolerance skills from Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (STOP and TIPP) help you survive the feeling of being criticized without immediately counterattacking. Mindfulness meditation builds the capacity to notice the threat response arising and pause before acting. Consider whether your current environment might actually require this level of vigilance; sometimes changing environments reduces the triggers. Mood stabilizers can lower baseline reactivity while you do the deeper work. The shift: from “I must control or I’ll be destroyed” to “I can stay present even when it’s uncomfortable.”

Resentment

The child who never got to say “no,” whose boundaries were bulldozed, who’s now watching others demand what they’ve never been given.

What it is. Resisting others’ boundaries because you never got to have your own. There’s a deep sense that boundaries being enforced against you is unfair – because it is unfair in some cosmic sense. Just the person who is doing it not is not the same who treated you unfairly. The resentment is displaced from its original target (often caregivers) onto current relationships.

The underlying wound. This pattern carries the weight of developmental injustice. If your boundaries were bulldozed in childhood – if “no” wasn’t permitted, if your space, body, feelings, or preferences were overridden – you learned that boundaries are things powerful people get to have and vulnerable people don’t. Watching others set boundaries activates that old wound: “They get to have what I never got to have.” The rage isn’t really about the current situation; it’s grief and fury about what happened to you, displaced onto whoever is currently asserting a limit. The wound is: “I was denied the basic right to boundaries, and it’s unbearable and humiliating to see others exercise that right against me.”

How it feels from the inside. When someone sets a boundary, there’s immediate, righteous anger. “How dare you.” It feels like they’re the one being unreasonable, unfair, selfish. There may be a sense of “rules for thee but not for me” – not as conscious hypocrisy, but as genuine felt injustice. Underneath, often inaccessible, is grief: the child who never got to say “no,” whose boundaries were bulldozed, who’s now watching others have what they never had.

Proactive form. A chronic chip-on-shoulder about boundaries and rules. Others’ boundaries are inherently suspect, probably oppressive, definitely hypocritical. You may be drawn to ideologies that frame boundaries as control or see yourself as a righteous transgressor of arbitrary limits.

Reactive form. When a specific boundary is enforced, fierce resistance: “You don’t get to tell me what to do.” The intensity is disproportionate to the situation because it’s carrying the weight of historical injustice, not just the present moment.

Toward recovery. Resentment requires grief – mourning that what you didn’t get to have. The rage is real, but it belongs to the past; therapy can help you direct it toward its true source rather than displacing it onto present relationships. Reparenting yourself includes learning to set your own boundaries now, which can reduce the envy of others doing so. EMDR and trauma processing can help metabolize the developmental injustice so it’s not constantly activated. Practice distinguishing past from present: “Is this person actually being unfair, or does it feel unfair because boundaries always felt unfair?” Self-compassion for the child who was bulldozed can coexist with accountability for the adult who’s now doing the bulldozing. Journaling can help you notice when the intensity doesn’t match the situation – that’s your signal that history is present. The shift: from “how dare they” to “their boundary is legitimate, even though I never got to have mine.”

A Final Note

If you see yourself in these patterns, please remember: These aren’t moral failures. They’re adaptations – once-necessary protections that have outlived their usefulness. Seeing them clearly is painful but essential.

Recovery doesn’t mean the patterns disappear overnight. It means you start to catch them, to feel the pull and choose differently, to repair when you’ve caused harm. It’s slow work, and it requires support – a good therapist, patient loved ones, and above all, compassion for yourself.

The fact that you’re reading this, trying to understand, is itself significant. These patterns thrive in the dark. Naming them is the beginning of change.

Read the whole post a couple of times. Very structured and insightful :)

I can testify to the benefits of Journaling and Meditation...

I have previously done good work on the idealisation one, and somewhat related to the entitlement one. This is interesting, I've never looked at that