The Sadism Spectrum and How to Access It

Is there a way to explain sadism? If it serves a purpose, is it still sadism? What types of sadism are there? How can you experience them?

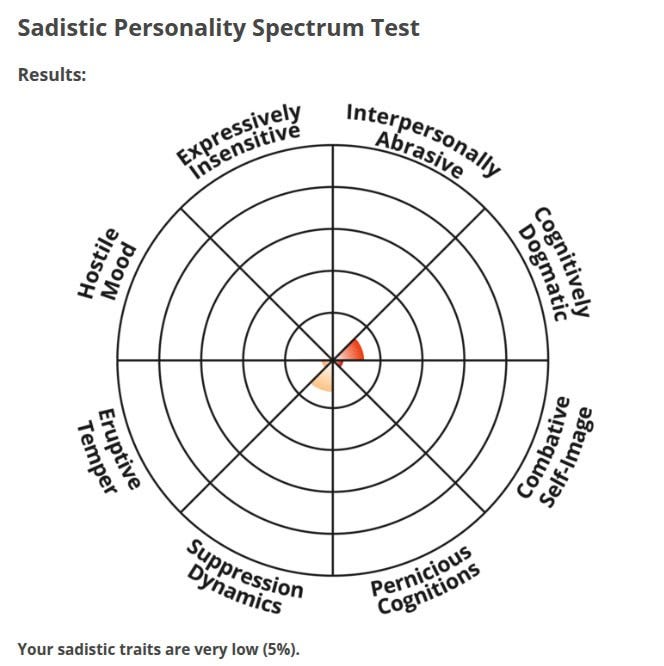

I’m on a quest to understand all aspects of human experience. But I found that I score really low on various measures of sadism – 2% in one test, 5% on another test, 7th percentile on a vaguely related test.

But I’ve made some progress! And if I can do it, so can you! If you too want to get a glimpse of what sadism is all about or want to understand your own sadism better, keep your eyes peeled (ugh?)!

Foundational or Assorted Sadism

Overview

Let’s start with the most difficult one: A direct link where some people experience pleasure as the result of someone else’s pain or humiliation.

If this simply has some kind of evolutionary origin, such as to enable hunting or fighting, I’ll call it foundational sadism. But it’s also well possible that there are more mechanisms mixed in here that are on the level of the individual’s personality development and that I just don’t recognize yet. The ones that I do recognize, I’ve separated out into their own sections.

Prerequisites

A prerequisite for sadism to work is to invert, sidestep, or lack in the first place any affective (emotional) empathy that would threaten to offset the pleasure from the inflicted pain:

One option is to inflict pain on someone who is masochistic and empathize with the pleasure they derive from the pain.

Another is to inflict pain with consent, so that the sub enjoys passively pleasuring the dom, and the dom can enjoy the sub’s enjoyment.

If someone hurts you or your friends, a kind of righteous anger, possibly hate, can flare up that also has a way of reducing empathy; that’s another way to unfetter sadism.

One can also practice dissociating from any feelings of empathy or care, which is perhaps just an ossified version of a permanent state of hate or disgust.

Finally, one can simply be born with certain atrophied and underactive brain regions, in particular the amygdala and insula. That often comes with a reduced experience of sensations in general and empathy in particular.

This is part of the reason that sadism ties in neatly with the so-called Dark Tetrad – Machiavellianism, narcissism, psychopathy, and sadism. (You can take the Dark Factor test to see how you score.)

Machiavellianism and sadism are hardly worth distinguishing in my view. The first puts a greater focus on personal gain, the second on harm to another. But as defensive adaptations, they serve similar purposes, and the “duper’s delight” associated with Machiavellianism seems to me just like a more intellectual version of general sadistic pleasures.

The link to narcissism becomes clearer in the section on control sadism and righteous sadism. But also resentful sadism can play a role because of how much the introjects of people with narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) limit their freedom to express or even to know themselves.

The link to psychopathy is two-fold. Straightforwardly, psychopathy is associated with reduced affective empathy, which helps to unlock sadism. But what Otto Kernberg calls “malignant narcissism” (and what I’ve termed “psychopathic narcissism” – these people tend to score high on behavioral measures of psychopathy too) is causally related to sadism is both directions. A basic sadistic drive is surely causal to why they develop this particular flavor of NPD, but it continues to serve them well to stabilize their self-image in ways that are unavailable to people with regular forms of NPD. I discuss this in more detail in Is Enlightenment Controlled Psychosis?

Causes

Apart from these prerequisites, there needs to be a positive reason to experience sadism.

Some of my friends report having experienced it for as long as they can remember, which is back to age 5, so long before puberty where some of them developed personality disorders. The foundations for these personality disorders were surely set in their earliest childhood, so this doesn’t rule out that their sadism is learned, but had it turned out to coincide with changes in their personality structure, I would’ve seen it as clearly linked to them.

For some, sadism also has a sexual component, and some paraphilias are already well developed around age 2–3. That context might hint at the rough age range at which sadism emerges. I’m still puzzled by why sadism has a sexual component for some sadists and not for others, so I won’t comment much on that distinction.

Some hypotheses of the etiology of sadism:

Sadism might be learned via marked mirroring when a parent reacts to the pain of the child with glee. The same parent is also likely to react to the pain of third parties with glee, but in an unmarked fashion, which will make it hard for the child to distinguish the emotion from their own.

Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder has this feature where people split on their perfection. If perfection is prosocial and interpersonal excellence, the negative split – which might take the shape of a paraphilia – may be sadism.

Sadism might also be an adaptation to defend against surivior’s guilt. Perhaps a child has to constantly witness violence or other injustices against a sibling or parent and adapts by taking pleasure in it, like a form of identification with a parental introject (assuming the aggressor is another parent). This is again exacerbated if the self-other boundaries are fuzzy.

Or sadism is a projection of masochism. A child experiences endorphin rushes as a result of pain and infers, via the typical mind fallacy, that others must enjoy pain just as much. A damped perception of pain is probably helpful for this. The boundaries between self and other are fuzzy for children in the first two years of life (and for some people well into adulthood), which could make it even harder for them to distinguish their own pleasure from any sensations of another.

Exercise

Whatever the origins might be, the next step for us is to investigate whether we can access it. For that we use the safe sandboxed environment of our imagination, conjure up someone we hate to reduce our empathy – such as a tyrannical dictator or someone who has hurt us sufficiently badly – and the experiments can begin!

If that is too difficult, you can try to feel out whether damaging or gaslighting objects induces any pleasure for you. After all, many people with personality disorders that come with psychopathic traits view other people more like objects than subjects. We can use the same trick by using literal objects. (And not feel so damn lonely along the way.)

For example, it sometimes happens that I’m being clumsy and something falls from my table to the ground. I might then pout and tell the object it’s its own fault it’s on the ground and that I refuse to pick it up, essentially gaslighting the object to rid myself of the responsibility for having dropped it. I don’t do that with people, probably because of interference from my empathy, my knowledge of the other’s mind (mentalization), and my fear of losing them if I piss them off.

For the purposes of our exercise, it can be helpful to test out, ideally mentally, whether harm to objects, be it physical or mock-psychological, elicits any pleasure for you.

Some people only experience physical or psychological sadism, so make sure to mentally experiment with both.

A friend of mine described Schadenfreude as “sadism with training wheels,” because it’s passive. Perhaps that is something you can access. There will be more (specific) examples below.

Control Sadism

Overview

Helplessness

Children are often helpless, powerless, dependent, which is a terrifying state to be in. They might compensate by proving to themselves that they can exert power over others, at least some others, by inflicting pain on them. It gives them a feeling of at least partial control and superiority.

If they’re more sure of themselves, they can go for subtler forms of control, like manipulating the other into wanting to do what they want them to do. If they have so much self-loathing that they can’t imagine anyone could possibly want to do something for them voluntarily, they’ll prefer more violent means.

If I feel helpless, I tend to hide behind guilt for something or other, usually almost everything, so I can trick myself into thinking that I could’ve affected it if only I had been better. Under that framing, I’m not helpless, or not if only I become better. It’s a reactive response to helplessness that has happened. All that guilt is misplaced and really paralyzing though.

Control instead is both preemptive and reactive. Preemptively, you’re in a constant state of hypervigilance looking out for opportunities to control others, for example, by lying to them and thereby controling their reality (these can be lies with no particular consequences for anyone); for opportunities to start, control, and end interactions on your terms, for example, by delaying them and finally ending them before the other does; or for opportunities to fool yourself into thinking that you’ve controlled someone, for example, by constantly performing ineffective actions that resemble manipulation and taking credit for any coincidental results.

But you can also wait until something happens that makes you feel helpless and only then start lying and manipulating to fool yourself into a feeling of having been in control of even such extremely challenging situations. If that fails, you can compensate by controlling someone else who is easier to control to prove to yourself that you’re not fully powerless.

Whether this takes the shape of sadism (harm to others) or Machiavellianism (gain for you) is perhaps a matter of personal taste.

Regular vs. “Malignant” Narcissism

Some people think, “I hate myself, but at least I’m better than everyone else” (regular NPD), whereas others think, “I have no self-compassion, but at least I’m more powerful than everyone else” (psychopathic/“malignant” NPD).

The key difference is that the first group defines themselves within society and its norms (which were foisted upon them through shame rather than introduced to them as reasonable contracts), whereas the second group sadistically hates and is enemies with society. That absolves them from the need to define their self-worth within the norms of society. Their self-worth is rather defined by whether they are winning or losing against society.

The first group is at war, internally, against their shame. The second group owns their shame and effectively projects it outward. If the shame manifests as a feeling of evil: “I’m evil; don’t look at me,” vs. “I’m evil; fear me!”

Whereas the first group is locked in an idealization-devaluation seesaw with (say) a romantic partner or a business rival, the second group is locked in an idealization-devaluation seesaw with all of society: “If I trick society, I’m God and society is my slave; if society domesticates me, society is God and I’m an ant.”

Interestingly, the first group has an easier time freeing themselves from their disorder – functional recovery – while the second group has more freedoms within their disorder. They are only bogged down by the shame from their introjects (see below), but they own their core shame. That allows them to self-deceive less about their motivations. I’m not sure if that’s functional recovery, but it’s certainly good enough that shouldn’t be decried as “malignant.” Many of my friends with this form of the disorder have found clever workarounds to lead prosocial lives despite all their restrictive armor.

Exercise

First you can test out whether it feels satisfying to you to lie to people about inconsequential things. Say, imagine your dentist asks you how you’ve been, and you make up a story about meeting a super cuddly cat on your way to the clinic. Does that already feel good?

If not, let’s make it easier: Come up with a memory of a time when you were defeated by someone. Maybe a time when a parent mistreated you, when you were outmaneuvered in a negotiation, or when someone stole from you.

Now come up with a fantasy scenario where you were prepared for the betrayal and had set a trap. Play it out in your imagination.

Maybe you’d invite the thief over for the first time but in this scenario you left some money strewn over your desk, seemingly at random. Except it’s precisely counted and photographed. You entrap them, confront them, and cut them off before they can steal more.

Or someone brake-checked you – but in your fantasy scenario you have a 4K dash cam that clearly shows the whole scenario including their license plate. Your insurance takes care of the prosecution, and you get a fat settlement in court.

Or someone spiked your drink – but in your fantasy scenario you noticed it, secured the evidence, and called the police. Once they’re in prison, you use a companion AI to start a penpal relationship with them, then waste their visiting hours by standing them up.

I hope you’ve been able to connect to this feeling of control sadism to some extent. It probably doesn’t come naturally to people with secure attachment, but perhaps it just takes particularly extreme situations, and then even they can access it to some extent.

Righteous Sadism

Overview

As the deeper motivations behind sadism become more apparent, the lines also blur between pleasure/relief that is directly caused by another’s pain or humiliation, and pleasure/relief that is achieved via another’s pain or humiliation but where something else is causal.

This category, which I call righteous sadism, is particularly blurry, (1) because pain/humiliation are a necessary concomitant, and (2) because some people really seek to indulge foundational sadism and use righteousness merely as an excuse to let loose.

Child abuse is widely considered to be an unpopular crime. It elicits sadistic urges in much of the population, and that is straightforward righteousness in most cases. But it is also unpopular among prisoners; among this population the share of those who don’t particularly care about the abuse itself and rather welcome it as an excuse to indulge their sadism against the perpetrator is surely greater.

One way or another, righteous sadism is tied to morality. If someone offends one’s own sense of right and wrong (or some pretend version of it), the response is often one of righteous wrath.

This gets more interesting when we consider that the rules of right and wrong that we’ve internalized vary a lot.

Many of us have internalized that abusing a helpless child is bad, but some have also internalized that showing vulnerability is similarly bad. Perhaps their parents punished them with abandonment until they stopped crying. (Or, perhaps worse, physical violence.) They didn’t take away from that that their parents were abusive assholes or even violent criminals (healthy) nor did these children take away from it that they themselves are evil (fusion with the inner critic) but rather that it was morally bad to cry (identification with the inner critic). Their abusive parent becomes what is called an introject. But the child refuses to feel the self-loathing the parent tries to install in them; they instead identify with the parental introject, learn to cry almost never at the threat of self-punishment, and punish others for crying just as their parents punished them.

The result is a quasi-sadistic urge to punish anyone who’s crying. Other common examples that can look like sadism are righteous anger (or possibly disgust) with those that reveal their vulnerabilities, admit mistakes, or behave differently in ways that are socially coded.

Many who feel these urges realize that they’re at odds with societal standards of politeness and try to fight them or channel their sadism into actions that cause no long-term harm.

Let’s break this down.

Attachment Styles

John Bowlby (Attachment and Loss, Vol. I) describes the basis of attachment styles as reliable or unreliable caregiver behavior:

If the parent is nonthreatening and attentive, that results in secure attachment of the child.

If the child doesn’t get the care they need, they sound the alarm (e.g., crying) so the parent remembers them and returns. If that works to keep the child alive, it results in preoccupied attachment.

If it fails and the parent doesn’t return, the constant alarm might attract predators, so the child hunkers down and tries to survive for as long as possible, fearing to be eaten by predators at any moment in their hostile environment. That’s avoidant attachment.

If the parent is also the predator, that’s disorganized attachment.

The parent who punishes the child with abandonment is likely to install avoidant attachment in them. The parent who punishes the child with violence is likely to install disorganized attachment in them. Either way, whatever they’re trying to teach the child gets hammered into them through traumatic conditioning.

Introjects

Many moral intuitions that we have are not so much evolutionary nor reasoned inferences from our ethical frameworks but rather conditioned emotional responses. These can take the form of introjects, such as parental introjects. That’s how an inner critic is formed.

A parent might condition a child to abhor lying or stealing or crying. A teacher might condition a child to abhor making language mistakes. A bully might condition a child to abhor revealing vulnerabilities.

Alfie Kohn’s Unconditional Parenting recommends not traumatizing your child to install this conditioning but rather to explain why certain behaviors are more effective than others.

The conditioning (roughly inspired by Object Relations Theory) can take different forms:

A child might identify with the introject, i.e. take on the moral commandments of the parent/teacher/bully as their own, adhere to them, and enforce them against others. That’s how many people feel about lying or stealing. Some religious conservatives feel this way about niche sexual practices even when they are conducted in private. I wonder whether this adaptation may be particularly common in the face of abuse of a sibling or perhaps one parent by the other, because it shields the child from self-loathing and from survivor’s guilt. After all, from the perspective of the introject, all the abuse are just deserts.

A child might fuse with the introject, i.e. feel self-loathing to the extent that they fail to adhere to them, measure themselves against them, but not enforce them against others. That’s how many people feel about financial or romantic success – they feel bad for falling short of what they think are their own expectations, but they don’t hate others for falling short. Most people feel this way about niche sexual practices that they don’t share so long as they happen elsewhere.

A child might rebel against the introject, i.e. they’re still controlled by the introject and are not following their authentic preferences and might even self-sabotage. They invert the control of the introject. An example is a person who was raised religious but then goes out of their way to burn bibles and have sex with a new friend each day despite not even enjoying sex that much. “Reverse psychology” exploits this reaction.

A child might avoid the introject, i.e. note the conflict between the doctrine of the introject and their own preferences, and avoid all situations where these can come into contact. For example, my introject said that I had to be maximally self-effacing. So whenever someone asked who wants to volunteer for some role or other, I stayed silent even if I would’ve enjoyed the role, because otherwise my introject would’ve punished me for thinking that there’s a chance I won’t fail at the role. I imagine many people feel this way about intervening in knife or gun fights. They feel that they should but don’t want to die, and so they rather stay far away from such fights so they don’t have to choose.

A child might project the introject, i.e. find a partner or boss who is as punitive as their parent or pretend that they are. I projected this role onto the top authorities at my school and the justice system of the country. Neither of them really cared about what roles I volunteered for, but because I never had contact with them, I could maintain the illusion that they did. Many people seem to be using God or the devil in this fashion.

Finally, there is healing, which requires becoming aware of the introject and what power it has over you, separating from it so you can question it, and finally self-compassionately reparenting yourself to replace it with a compassionate voice.

For the awareness part, I find it helpful to watch out for absolutes such as “I would never” or “I always.” Think of instances when you would or wouldn’t. Maybe come up with harmless ones and practice them.

Immanuel Kant, widely regarded as one of the world’s most influential philosophers, strongly believed that lying is the wrong thing to do in absolutely every circumstance. The “murderer at the door example” is an attempt to challenge Kant’s view by displaying a situation where someone hides a friend, who is about to get murdered, in his house; then, when the murderer appears at the door, the question arises on whether the homeowner should lie, in order to protect his friend, or tell the murderer the truth, because the truth must always be told.

If you’re ever in that situation, please lie.

Exercise

Can you think of someone who’s done something abhorrent? Maybe your tyrannical dictator of choice? Guards at concentration camps? Or these murderers? If you fantasize about hurting or humiliating these people, does it feel like justice?

If not, maybe you need something more clever. In some episodes of Columbo, the detective recognizes the M.O. of a murderer and uses it in some creative way or role-plays the perfect victim. But it’s a trap, and usually he has backup standing by for his safety and as witnesses for the murder trial. Does that feel more exciting?

Resentful Sadism

Overview

Let’s introduce our fictional friend John Christensen, who is homosexual in an environment that rejects homosexuality. He goes to great pains to refrain from ever engaging in any homosexual pleasures. He censors his thoughts and bans himself from enjoying any homosexual fantasies. Sometimes he slips up and punishes himself harshly for his perceived thought crime. He is tormented by guilt and shame over his thoughts and begs God for forgiveness, but most of the time he can hold them at bay and feels virtuous about that. He feels virtuous for the severity of his self-punishments too. For decades he conditions himself in this cycle of virtuous thought discipline, shameful slip-ups, and draconian but virtuous self-punishment. (Eventually he marries a woman who’s a sex-neutral asexual and he pretends to be the same. They share a strange bond they don’t quite understand, and they bond over their religion too.)

Then he meets Kim and Rowan who are openly gay and have kinky fun at the Folsom Street Fair. They don’t hurt anyone, in fact they are kind and helpful neighbors. God hasn’t burned down San Francisco either, nor turned them into salt statues. They’ve even adopted the child of someone who couldn’t get an abortion.

Now John has to choose to either hate them and maybe fantasize about them burning in hell, or to acknowledge that he has tortured himself all his life for no reason. Resentment or grief. Not a fun choice.

Some choose resentment and implement it in sadistic ways. (In philosophy they seem to prefer the French translation ressentiment.)

Another common example is displaying vulnerability. If someone was never comforted as a child when they cried, and now they see someone crying in public, maybe that’s not so bad yet (unlike with righteous sadism), but if that person turns to them for comfort, it can feel unfair. How dare this person ask of me what I was never given?

I intuitively project my inner child on people who are suffering in such ways and welcome the chance, through this illusion of time-travel, to give to myself what I wasn’t given. Perhaps a holdover from my days of borderline personality organization. From a neurotic perspective, feeling resentment and unfairness in such a situation seems natural enough.

Again, many fight these urges to punish, or they channel them into mostly harmless actions.

Exercise

When did you last feel resentment?

At my elementary school, especially starting around 2nd grade, there was a lot of violence, especially by boys perpetrated against girls. I was too afraid for my own safety to intervene and for decades was tormented by the guilt over my inaction. I do better today, but people who turn a blind eye to violence and show no signs of similar torment still cause me to feel resentment. Some part of me wants them to suffer similar survivor’s guilt. Another part of me wonders whether that is quite the right approach or whether I should’ve been more self-compassionate from the start.

I was also punished a lot for accidentally dropping or spilling things (even though it happened very rarely), so I still have an outsized emotional reaction to cats even intentionally trying to drop things off tables. This anti-cat table gives me sadistic tingles.

Did you find a similar source of resentment? Does it also cause you a mix of feelings, at least some of which resemble sadism? Congrats!

Vindictive Sadism

Overview

Vindictive sadism is pretty straightforward: Someone hurts you or yours, and you feel an urge to hurt them back. Revenge, reprisal, retribution. Justice system of the world seem to be mostly based on this intuition.

It is probably meant to serve as deterrence, but there’s a difference between the visceral motivation that someone feels to enact revenge and the function it happens to have, whether they’re aware of it or not. Contrast that with a judge who thinks that they have to sentence someone to a long prison sentence not because that particular person has been so vile but in order to deter others. That is a much more calculated decision.

Exercise

Been hurt by anyone recently? Or maybe a family member or a friend? Does that make it easier to derive pleasure from fantasies of hurting them back?

If not, what about a kind of punishment that particularly attuned to their affront? Say, if someone’s M.O. is to tell just the right lies to the right people to isolate people and break up relationships, and then they try it on you and your partner and fail humiliatingly because of how much you trust and know each other – how about that?

Contumacious Pride

Overview

Running with such an obscure word for this one is apposite because when people tell me I should’ve just called it “stubbornly rebellious pride,” I can go “No!” to demonstrate what it means:

Legal contexts are one area where you might encounter this fancy word for “rebellious” or “insubordinate” – and the link between contumacious and the law goes back to Latin. The Latin adjective contumax means “rebellious,” or, in specific cases, “showing contempt of court.” Contumacious is related to contumely, meaning “harsh language or treatment arising from haughtiness and contempt.” Both contumacious and contumely are thought to ultimately come from the Latin verb tumēre, meaning “to swell” or “to be proud.”

This is a bit of an odd one, but I think it’s closely related to righteous and vindictive sadism. People often expect others to be like them, and if they find pleasure in vigilante justice and retribution, they’ll expect others to be the same. They’d even be right when it comes to the judicial system, except the judicial system probably doesn’t have an internal conscious experience.

This typical mind fallacy leads to a very antagonistic view of the world. One where all people are enemies or competitors, where there are only winners and losers, where might makes right. A world where there is no cooperation for the sake of social norms but only if it generates gains from trade – which is silly because social norms are exactly what enables gains from trade in collective prisoner’s dilemmas and assurance games, but that’s hard to see until you’ve destroyed the social norms and find yourself much poorer.

Under this framing, it makes no sense to think in terms of remorse and penance. When you go to prison, it just means your enemies won this round. Perhaps you made a mistake, but it was merely a strategic mistake, not a moral mistake. It’s a cost, like a tax, you have to pay from time to time.

Some people like to travel a lot, and so they might get sick more often from all the different viruses they encounter. That’s also not a punishment for traveling – it’s just a momentary defeat, perhaps a strategic mistake if they should’ve known enough epidemiology to know how to protect themselves, perhaps it’s just a cost they have to pay from time to time.

So just like these travelers will think, “Diarrhea sucks, but I can get through this. I’m strong. And I love traveling enough to put up with this,” so someone with contumacious pride may think, in the spirit of good sportsmanship, “I got back at five of my enemies and embezzled $100k along the way. That’s worth 2 years of prison for me, and I got only 18 months. That’s fair.” Or without the sportsmanship, “If they think they can break me with 15 years, they have another thing coming. These jury members don’t know that these 15 years are their last.”

It’s the same spirit of sadism but from the perspective of a victim who is a sadist themselves.

Imagine someone like that involved in a restorative justice process. If they don’t dismiss it as a farce, or as other people just being so much worse than they are at vengeance, then it must be quite disorienting to them because it breaks their antagonistic view of others.

Exercise

Are you a member of any kind of minority group and out of the closet and proud? Perhaps you’ll encounter people of different moral persuasions who think you’re bad, should be illegal, or that you don’t exist in the first place.

Perhaps they can still hurt you, or perhaps you feel vicarious embarrassment for them, but perhaps they also make you feel strong and make you wish you had flaunted who you are even more visibly because it excites you how much you can infuriate them by just being you, no effort at all.

If so, you’ve managed to tap into the spirit of contumacious pride.

Antisocial Punishment

Overview

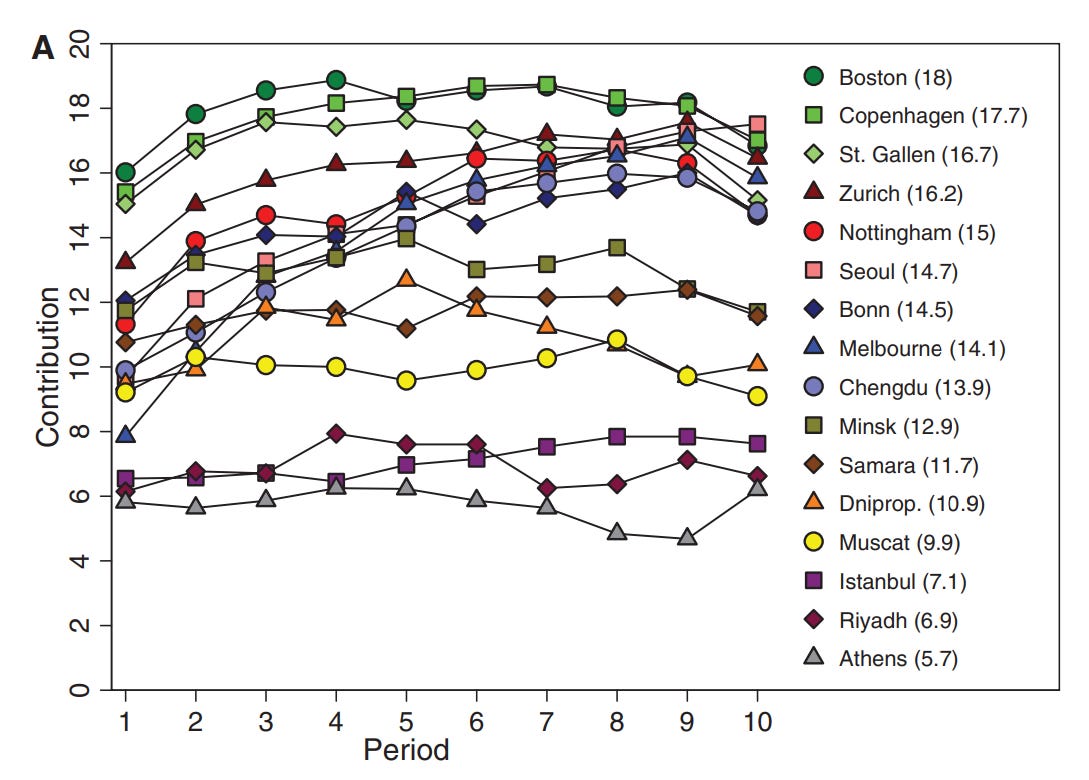

There seem to be three “cooperation” strategies out there in the wild as shown by the public goods game that a team of researchers conducted across 16 cities worldwide.

A public goods game with punishment is an iterated game theory experiment where participants contribute to a common resource, but can then incur a cost to punish others who do not contribute enough (free-riders). Punishment, though costly, is shown to increase cooperation and group contributions over time by discouraging free-riding, though the effectiveness can vary across cultures and can sometimes result in “antisocial punishment” where cooperators are punished by non-cooperators. (Summary courtesy of Gemini.)

In one strategy (exemplified by Boston, Copenhagen, and St. Gallen), all participants contribute to a high degree from the start. I think this corresponds roughly to how tit-for-tat agents cooperate with each other from the start. It requires that it’s known what cooperation means, i.e. what the expected behaviors are.

In the second strategy (exemplified by Melbourne, Seoul, and Chengdu), participants don’t cooperate much at the start but then punish each other for it and cooperate at high levels after a few rounds. This resembles the behavior of Pavlov agents. When you don’t know what is expected of you, the best you can do is to fuck around and find out.

Finally, there is a bit of an antistrategy (exemplified by Athens, Riyadh, and Istanbul), which simply doesn’t work. People punish cooperators at high rates and thereby harm themselves and everyone else. Why would anyone think that’s a good idea?

I think part of the answer is perhaps simply that people punish those who are sufficiently different from themselves. Punishing defectors is a more complex strategy than punishing those who are different, so absent a clear idea of what defection means, being different has to serve as the closest proxy.

But another explanation is that cooperating is seen as something costly that only those of high status and strong character can afford. These are desirable qualities that only few possess and that make these few highly coveted cooperation partners. Everyone else feels threatened by these few and tries to fight them to improve their own relative standing. Because the cooperators are few and the defectors/assailants are many, the cooperators surrender and turn into more defectors.

This is something that I understood intuitively as a child. The lowest social status is the safest because no one will try to take it from you. The highest social status is the most precarious because everyone wants to take you down or knock you off the throne.

Put this way, it sounds like just another form of instrumental sadism. But I don’t think the people who exercise it think of it in quite the same strategic terms. More likely people associate some kind of negative stereotype with cooperators. Imagine Cordelia Chase from Buffy the Vampire Slayer, but instead of showing off with expensive clothes she shows off with big charity donations. I also really appreciate her character arc throughout the show.

Exercise

As so often there are probably few among us who can understand antisocial punishment directly. But as it happens, I met a new friend the other day who was irked by friends of hers who rented out a castle and put on expensive dresses for a photo shoot whose goal seemed to have been to make friends of theirs jealous and/or envious who’d see the photos on social media.

Viewing friendships as a kind of status competition that includes cheating, such as posing on strangers’ cars for photo shoots, is strange to me, but while I find it rather quaint, perhaps it is the kind of status signaling that resembles how people in Istanbul and other places feel about cooperators and why they want to punish them.

There are also plenty of fictional examples where the audience is expected to find a sadistic pleasure in the downfall of a prideful ruler. I can empathize with it in some cases. You can scan the titles and examples for shows or movies you know and see if you can access the feeling too.

Instrumental “Sadism”

This is the catch-all category for all the forms or aspects of sadism that are not actually sadism.

When someone takes revenge publicly on a colleague, it could be partially motivated by vindictive sadism and partially by purely instrumental deterrence. If someone works at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp to torture secrets out of prisoners, it could be that they’re partially motivated by foundational sadism and partially by keeping their job and getting their salary. If someone works as a surgeon, it could be that they’re partially motivated by foundational sadism and partially by saving lives.

Perhaps there are also some forms of purely instrumental “sadism,” but it’s probably sensible to remain suspicious of those and question whether there’s not some actual sadism behind them after all.