Evidential Cooperation as a Black Box

What if there’s finally a way to answer ethics’ age old question of how one should act? What if we can cooperate with countless beings to generate enormous gains from moral trade?

What if there was a way to cooperate with beings we will never meet? Beings in other galaxies, other universes, or other Everett branches? What if this cooperation could help us achieve more of what we value – whether that’s creating flourishing societies or alleviating suffering – on a scale vaster than we can imagine? This is the tantalizing promise of Evidential Cooperation in Large Worlds (ECL).

This post won’t address how ECL works. For those who want to explore the machinery under the hood, the Center on Long-Term Risk’s ECL overview page is the definitive resource.

Instead, we’re going to treat ECL as a black box. We’ll focus on what it does for us, the assumptions it requires, and the limitations it faces.

What ECL Does for Us: A New Ethical Compass

At its core, ECL offers a potential framework to answer one of the oldest questions in ethics: How should one act?

You put in your research on what you think the distribution of values are across the universe.

You put in what the part of the universe is like that you have access to.

It returns a recommendation for the optimal actions you should take to maximize everyone’s values, including your own, across the universe.

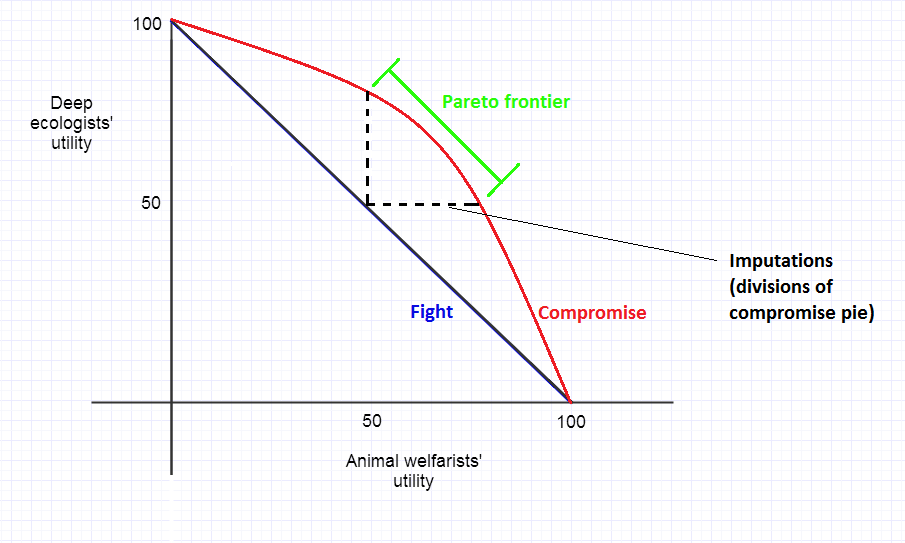

The key insight is that this cooperation creates Pareto improvements on a cosmic scale. Imagine two civilizations: One is full of easily preventable suffering but no one cares. The other is full of people who care about reducing suffering but has a very small population and the remaining sources of suffering are costly to eliminate. Under ECL, the civilization with more suffering will reduce suffering because they trust that that means that elsewhere in the universe someone else will maximize something that they care about. We are all better off.

ECL does this in a way that can be satisfying to both moral realists and antirealists:

For the antirealist, who may not believe in a single, objective moral truth, ECL provides a framework to fully answer the question of ethics. It’s about engaging in a form of moral trade to achieve outcomes that all parties prefer.

For the realist, who believes their values are correct, ECL and moral trade in general are powerful tools to maximize those values. It’s not about agreeing on what is “right” but what is effective. It doesn’t answer their question of ethics but it nonetheless tells them what to do.

Either way, it suggests that by acting cooperatively, you can learn that a vast number of other agents across the multiverse act in ways that benefit you.

The Fine Print: ECL’s Foundational Assumptions

The promise of ECL is grand, but it rests on an few assumptions that, while largely mainstream, have their detractors.

The universe is large enough (possibly infinite). The framework relies on the existence of a vast number of other agents to cooperate with. This could come from a spatially infinite or extremely large universe (flat with infinite matter), the countless “bubble” universes proposed by cosmic inflation theories, or the branching realities of the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics. Without a vast sea of agents, the potential gains from acausal cooperation dwindle.

Our choices are evidence. ECL treats your rational decision-making process as a piece of evidence. This idea stems from non-causal decision theories, which are still somewhat contentious.

We can solve Infinite Ethics. The possible infinity of the universe is both beneficial for ECL but also a problem, the same way it is a problem for all forms of aggregative consequentialism. ECL assumes that we can apply a workable solution – perhaps one proposed by Nick Bostrom – to salvage all forms of aggregative consequentialism.

The Catch: Limitations and Open Questions

Even if we accept the assumptions, ECL does not yet make hard-and-fast recommendations.

It’s never fully knowable. How do we know what a distant alien civilization or a future superintelligence truly values? We can make inferences from convergent drives, evolution, and our values, but they may be different from the inferences other civilizations will make.

It requires deep research. Much modeling and empirical research is still needed to make these inferences and refine them.

In the end, ECL is a promising avenue toward solving ethics. It suggests that the most rational way to act may also be the most cooperative, and that the scope of our moral community might be as large as reality itself. It’s a call to think bigger, to consider the possibility that our choices echo in ways we can’t see, and to invest in the foundational research that might one day tell us if this cosmic bet is one we should take.