Breaking the Cycle of Trauma and Tyranny: How Psychological Wounds Shape History

A developmental perspective on authoritarian leadership and how we can build more resilient societies

Introduction

Five years ago, David Althaus and Tobias Baumann published a delightful article “Reducing long-term risks from malevolent actors.” It focuses on the risk factors that “malevolent actors” pose when it comes to long-term catastrophic effects on civilization.

Large parts of the article are devoted to the screening for 99th percentile “Dark Tetrad” traits – traits of Machiavellianism, narcissism, psychopathy, and sadism. For comparison, I’m in the 7th percentile according to the “Dark Factor” scale.

I think there are many more places where we can intervene.

I propose a circular model where:

Wars and societal collapses cause widespread trauma,

Which causes widespread insecure attachment and personality disorders.

People with these mental health problems grow up, and because they’re desperate for power and admiration, they form a large pool from which new authoritarian leaders are likely to emerge.

These are then a risk factor for further wars and societal collapses, perpetuating the cycle.

This model suggests four points at which we can intervene to break the cycle.

I feel deep compassion for the people who are suffering from these personality disorders, so closest to my heart are interventions that prevent them from emerging in the first place.

It should be noted that none of these interventions will show results within a few years, so all of this is only relevant in worlds in which, by some miracle, the AI thing goes well.

Dolores

To humanize the discussion, let’s introduce my fictional composite friend Dolores. She’s loosely inspired by real friends of mine who score high on all four traits of the Dark Tetrad. I’m hoping to show that there is no such thing as evil, but rather that children find quite brilliant adaptations to the extremely challenging environments they are trapped in throughout their childhoods. These can heal in adulthood (when they gain their freedom) in the same way that someone who has lost a foot can learn to walk again with a prosthesis. It often takes only a few years of therapy.

Dolores is an example of someone with NPD and ASPD. Someone with pure ASPD/psychopathy would be less concerned about upholding any particular characteristics of their personality, and someone with pure NPD would try to self-deceive more comprehensively to hide from themselves any of their behaviors that violate their self-image including values.

Psychopathy. Some of Dolores’s ancestors served in World Wars I and II. Others tried to raise children among the dropping bombs. Dolores’s dad worked long hours to provide for the family and his alcohol addiction. She hardly remembers him. Dolores’s mom never showed emotions other than occasional anger and disappointment and thought that emotional empathy was some kind of metaphor because she had never experienced it.

This personality aspect references war and its effects on epigenetics and how trauma is passed down through parenting practices.

Pathological narcissism. Her mom tried to care for her to the best of her limited ability, but Dolores’s twin sister was born with a disability and required all her attention. For a while Dolores cried a lot when her mom was elsewhere seeing doctors with her sister or drinking in her car to unwind. Then Dolores stopped crying for good. Her mom often told her how great it was that she, unlike her sister, never needed any support, was always strong, independent, and in charge, and eventually Dolores started to believe it too. Any feeling of tiredness or sickness or physical injury filled her with unbearable shame like she was unworthy to even be alive if she felt such things. It was so unbearable she repressed it with rage, often within seconds. She must never be weak or dependent on anyone. It wasn’t so much anymore that she didn’t want to disappoint her mom. Rather her mom’s expectations had become her own. They felt like natural law.

This narcissistic false self is (on account of being false) often at odds with reality and requires constant maintenance, for which fame, power, achievement, admiration, and money are useful.

Sadism. She found that if she started fights, the adrenaline pushed those unbearable feelings away, and she felt invulnerable again. To an extent she was, because it was easy for her to ignore any pain and she didn’t need much sleep. But to acknowledge the reason for her misconduct would be to acknowledge her vulnerability, so she told herself that she just righteously punished people for being weak. It wasn’t even a lie. She resented people who showed weakness the same way others resent cheaters. A boy cried because he had sprained his ankle, which had happened to Dolores many times before. One teacher consoled him and another ran to get ice. It made her boil with righteous anger because the alternative would’ve been to feel envious of him, which was unbearable. Once he could stand up again, she tackled him to the ground and dislocated his shoulder so he had something to cry about. She relished his pain and fear and wondered whether she was an archangel sent down to enact the wrath of God. She felt not only powerful, she felt valiant for defending the law of God and merciful because she had long been taking a knife to school but had chosen not to use it.

This kind of righteousness, like any kind of righteousness, is a breeding ground for conflict. (Interestingly, pure psychopathy is unusually immune to this kind of righteousness, which may reduce the risk of some kinds of conflicts.)

Machiavellianism. But then middle school (and her puberty) started and she became the target of older, stronger bullies who made fun of her second-hand clothes. She didn’t care about the clothes, but she would rather die than to not be in charge of a situation like those wretches she had punished. At home she was subservient and invisible; in school she was the punisher. Neither pattern was suitable to respond to these bullies. So she got out her knife, stabbed herself in the shoulder (she felt she had deserved the pain anyway for her weakness), and hid the bloody knife in the bag of the lead bully. Then she reported him to the principal. After a few days of well-rehearsed lies and affected sobbing, the bully got expelled. It was delicious vengeance, but more importantly she relished the ability to control everyone’s realities with her lies. She started to lie habitually so she would always feel in charge. People who are dumb enough to fall for her lies had it coming. But she also enjoyed helping others with their homework and covered for them when they wanted to skip classes. It felt safe that everyone was a little indebted to her, which she could leverage to bolster her popularity and get away with stuff more easily. But she also relished simply being seen as a good person.

In a war zone you don’t walk up to your enemy and complain about the shooting. But she hadn’t had the chance to learn how to function in an environment where assertiveness works, so she had to fall back on her wits. This can be adaptive in the dog-eat-dog world of politics.

Recovery. Shortly before her 18th birthday, she found herself once more in a juvenile detention center for a colorful panoply of alleged crimes – assault, theft, identity theft, possession of illegal drugs, trespassing, driving without a license, driving under the influence, reckless driving, etc. She was sure she would walk free again, because she’s a genius manipulator who can charm her way out of anything. But she could no longer repress the thought that it was perhaps just her age that had protected her from prison sentences. The thought was heavy as a tank and cut through her like a sword. Acknowledge that she can’t control the justice system, go to prison, or kill herself in a final act of defiance? She remembered Ken Follett’s Eye of the Needle, in which an elite spy and assassin with near superhuman skills plays the roles of meek and ordinary citizens to draw no attention behind enemy lines. She could also use her genius and guile to play the role of a model citizen and thereby trick the entire social contract. Her final triumph on her path to complete mastery of social engineering!

But she had to cleverly devise other outlets to get her adrenaline and to continually prove to herself that she’s invulnerable and in charge. Within a year, she excelled at rugby and broke into abandoned buildings at night. Just like the alcohol, it made her life feel a little less empty and gray. Whenever she followed a law so as not to risk prison, she felt like Ken Follett’s cunning spy.

Her problems with the law became minor, but somehow it was still difficult for her to keep friendships for more than a year. She ruminated a lot on her lost friendships even though she felt nothing and always told herself that she doesn’t need anyone. She limited her lies to untestable and inconsequential things so she could still control her friends’ realities but only in ways that didn’t clash with the actual reality. When her friends cried, she stormed out of the room and distracted herself by running people over in Grand Theft Auto so as not to punish her friends for their weakness. Sometimes she punished them by ghosting them for a week, but on some level she knew they’d just think she’s busy. She finally managed to keep some long-term friends – friends who considered her a good, strong, and reliable person.

Years later she started therapy, ostensibly to manage her alcoholism. She quit on or ghosted her first eleven therapists, but the twelfth was a hottie and she gave him a chance. All the lies she told her therapists shaped a persona wholly different from her real self. She told herself that she’s testing their intelligence and hence worthiness to treat her, but really she had never opened up to anyone and was terrified of what they might force her to acknowledge if they knew more.

Over the course of two years, she lied more and more glaringly on purpose hoping he’ll finally catch on. She was ready now, but she still needed to maintain the illusion that she had been testing him because there was no way she could acknowledge having been afraid. Eventually she had enough, screamed at him that she had been lying to him all along, fought back oh-so-shameful tears by throwing her phone against the wall, and then told him what he really needed to know.

Self-awareness was weird for her. Even after another two years of therapy, all her self-deceptions felt just as real to her as always, but now she knew that they were not. These two realities refused to fuse. Maybe it wasn’t time yet and still too threatening. It became easier for her to realize when she had to override her intuitions, which was helpful in her friendships and at work (though the realizations were sometimes a few days late), but her intuitions corrected themselves only ever so slightly. She got diagnoses for NPD and ASPD and learned that other people actually experienced strange sensations like empathy and remorse, that it wasn’t all just pretense. She could also think more strategically about how to self-soothe, explain things to her friends, adjust her environment, replace destructive coping methods with better ones, cut off toxic people without taking revenge on them, and find jobs where her rare adaptations could serve prosocial ends.

Alternative ending. But there is a different world where Dolores didn’t self-deceive into pretending to fool the justice system with her masks but rather vowed to avenge the indignities she had suffered at the hands of the executive and judicial branch. Her plan might’ve involved writing a long list of the names of every employee of the courts and prisons who had limited her freedom, becoming a political leader or starting a military coup to destroy all democratic checks and balances, and personally condemning everyone from her list who’s still alive at that point. But in that world we likely wouldn’t have met.

Attachment

Our attachment styles – our early-life strategies for securing safety and connection – form a blueprint for our relationships throughout life. There are four primary styles:

Secure: A baseline of trust in others and a sense of self-worth. This fosters resilience and comfort with interdependence.

Preoccupied (alias anxious): A preoccupation with relationships and a fear of abandonment, often leading to a desire for validation from others.

Avoidant (alias dismissive-avoidant): A prioritization of independence and self-reliance, often at the expense of emotional intimacy, stemming from a core belief that depending on others is unsafe.

Disorganized (alias fearful-avoidant): Resulting from experiences where a caregiver is a source of both comfort and fear, this style involves a painful mix of wanting and fearing closeness. It creates significant internal conflict and a powerful need for control to manage this chaos.

All attachment styles other than secure are also collectively referred to as insecure attachment.

This framework is not just for romantic relationships; it shapes our relationship to society, authority, and ourselves.

The Psychology of Followership

Dolores’s attachment style is highly avoidant and only mildly preoccupied. Avoidant attachment is very typical of NPD and ASPD.

How does a leader with these psychological adaptations gain a following? The appeal can be understood as an interaction between the leader's psychology and the collective attachment anxieties of a population. An authoritarian leader can function as a powerful external regulator for a populace feeling destabilized.

To those with anxious tendencies, a leader’s promise of “I alone can fix it” offers powerful relief from uncertainty.

To those with avoidant tendencies, a leader’s transactional approach and disdain for the perceived “weakness” of empathy can be seen as signs of strength.

To those with collective trauma, a leader who validates their sense of grievance provides a channel for their rage, which can feel deeply empowering.

Breaking the Cycle

Breaking this pernicious cycle requires a multi-layered strategy, acting on individuals, institutions, and our foundational knowledge. The following combines the developmental approach of this article with several institutional and long-term proposals from David Althaus and Tobias Baumann’s work. I’ve added to each strategy areas of expertise that are likely required to pull them off.

In general, we want to optimize for something like Aaron Antonovsky’s “Sense of Coherence,” a measure of good mental health:

Comprehensibility. The belief that the world around you is structured, predictable, and makes sense. Events aren’t random and chaotic; they are explainable.

Manageability. The belief that you have the resources (either your own, or available from your family, friends, or community) to meet the demands of life. The feeling that “I can handle this.”

Meaningfulness. The belief that life’s challenges are worthy of investment and engagement. This is the motivational component – the feeling that it’s worth it to try.

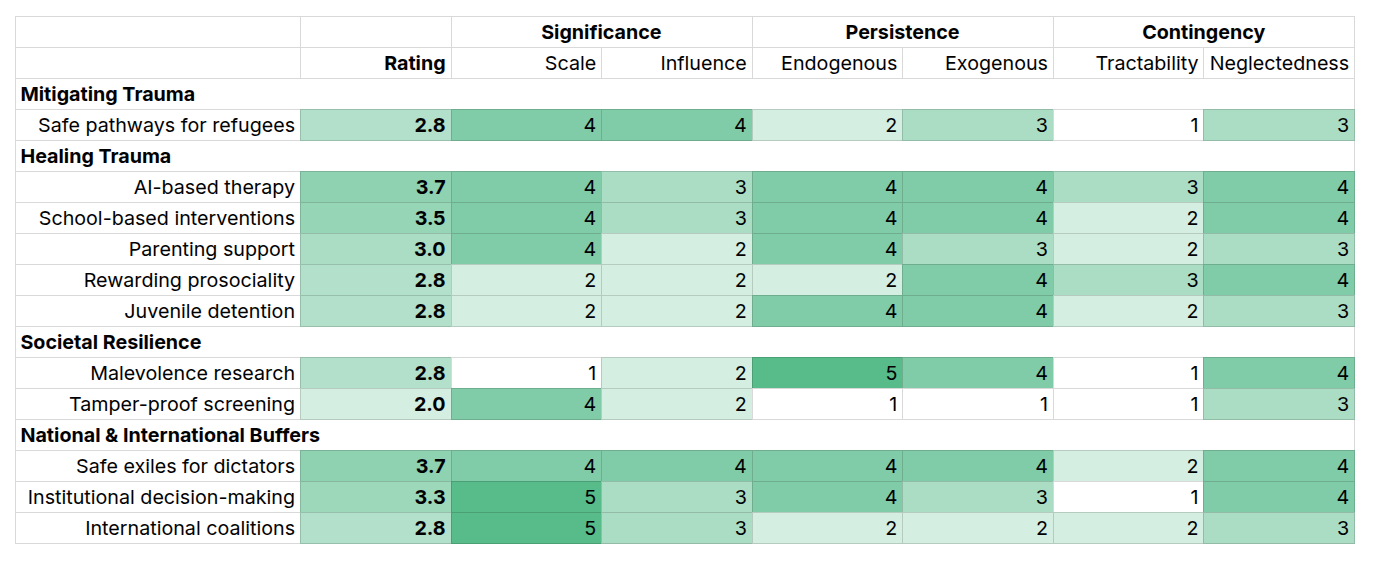

I’ve tried to guess very roughly where, on a scale from 1 to 5, I see each intervention area. I’ve broken this down first according to the significance-persistence-contingency framework and second according to my own subdivisions.

My intuition is that AI-based therapy, school-based interventions (merged for simplicity), safe exits for dictators, and improved institutional decision-making are the greatest levers. But not by a great margin. Opportunism and personal fit will likely make the decisive differences.

Mitigating Trauma

Safe pathways for refugees. Currently it’s an often deadly and tremendously traumatic affair to try to emigrate from a country that is at war. The UN Refugee Agency and others advocate for safe and regulated pathways for refugees.

Politics, policy, activism

Healing Trauma

Parenting classes. If we intervene in high schools and teach state-of-the-art practices of good parenting, we can break cycles where children learn harmful practices from their parents and pass them down. Even adolescents who will continue to suffer from personality disorders that tend to be passed down can force themselves to treat their children better than their intuitions would have them.

Policy, schoolbook publishing, pedagogy, psychology

Mental health classes. Good mental health practices are often learned, and that learning could happen in school rather than in the therapy sessions of only those who seek therapy.

Policy, schoolbook publishing, pedagogy, psychology

Values classes. Compassion, rationality, assertiveness, and radical acceptance are key to the recovery from NPD and ASPD. Furthermore, NPD is sustained by self-deceptions that are at odds with rationality and sometimes compassion, so these values can make it easier for sufferers to recognize their self-deceptions.

Policy, schoolbook publishing, pedagogy, psychology

AI-based therapy. Mental health classes may be both too hard to establish and not sufficiently focused on the individual. But perhaps the rollout of individual AI-based therapy for every pupil is more realistic and focused. AI-based therapy can also offer a non-judgmental first step for individuals who, like Dolores, may not trust human therapists. “The Kauai Study” found that a strong bond in childhood with at least one mentally healthy adult is critical for the mental health of the child, and perhaps an AI can provide this bond for children who know no mentally healthy humans.

Psychology, software engineering, policy

Parenting support. Policies that reduce parental stress – such as paid parental leave, affordable childcare, and home-visiting nurse programs – interrupt the transmission of trauma and foster secure attachment.

Psychology, policy

Juvenile detention. Many people who’ve recovered from ASPD say that prison sentences (sometimes several) have been invaluable for them and that they wish they had been caught and gone to prison earlier than they did. In this way, juvenile detention is perhaps an effective de facto therapy of ASPD that can intervene early in a person’s life. Ideally the criminal record should expire to not limit the person when they’re trying to turn a new page.

Policy, politics

Rewarding prosociality. People with NPD can have a highly prosocial self-image that motivates them to change the world for the better. They often lack an internal feedback mechanism that rewards them when they’re doing a good job, making them dependent on external feedback. Stronger norms to publicly and frequently reward prosocial behaviors could have an even greater positive effect on people with NPD than on the average person.

Philanthropy, activism

Societal Resilience

Secure attachment. As described above, a populace with largely secure attachment is less likely to be receptive to disordered messaging.

See previous section

Sense of coherence. As described above, a populace with robust mental health and resilience.

See previous section

Egalitarian social norms. Authoritarian leaders will ring false to the ears of a populace that values flat hierarchies.

Unclear

Malevolence research. Althaus & Baumann call for a focused research program to develop better constructs and measures for the traits that cause the most harm. A deeper understanding of the neurological and psychological underpinnings is a prerequisite for effective interventions.

Psychology

Tamper-proof screening. A key proposal from their work is the creation of reliable, manipulation-proof measures of malevolence. These could one day be used to screen for high-risk individuals in positions of immense power, such as heads of government or leaders of critical global institutions.

Psychology, policy

National and International Buffers

Better institutional decision-making. As Althaus and Baumann note, classic political science solutions are a vital complement to psychological ones. This includes strengthening democratic checks and balances, promoting measures to reduce political polarization, and supporting a well-resourced, independent press.

Policy, politics, activism, journalism, law, sociology, economics

International coalitions. Elegantly constructed international coalitions and contracts can increase the stability of the whole worldwide system.

Policy, politics, activism, law, sociology, economics

Safe exiles for dictators. Some dictators want to retire at some point but can’t because they need the power of the state to prevent attempts on their lives. Providing them with a way in which they can cede power without being killed may increase the chances that they’ll negotiate a transition of power.

Military, politics, policy

Risks

Lack of psychopathy. People with secure attachment and without any personality pathology can still be zealously righteous about whatever tribal moral goals they subscribe to. That’s also a risk factor. People with pure psychopathy may in fact be unusually immune to that, thereby unlocking gains from moral trade.

Naïveté. Maybe peace is better kept and more stable by maintaining a balance of highly manipulative and power hungry people on all sides, the same way some people argue that nuclear war is better prevented by maintaining a balance of sufficiently large well-maintained nuclear arsenals in the hands of many countries around the world.

Discrimination. Some measures risk exacerbating the discrimination against perfectly prosocial people suffering from personality disorders.

A Call to Action

Talk to me if you have access to any of the relevant fields, and maybe we can strategize.

Do you know any organizations that are working on this?

Protect yourself but also be patient with people with personality disorders. They can heal and use their skills for prosocial ends.